Ever since 1960 the European champions have met the top team in South America for a trophy called the Inter – Continental Cup. That name is hardly ever used, however, as everyone accepts that this home and home fixture is for the World Championship – the supreme status symbol in club football. So I imagine there ate lots of youngsters in many countries who dream of playing in these very special show games.

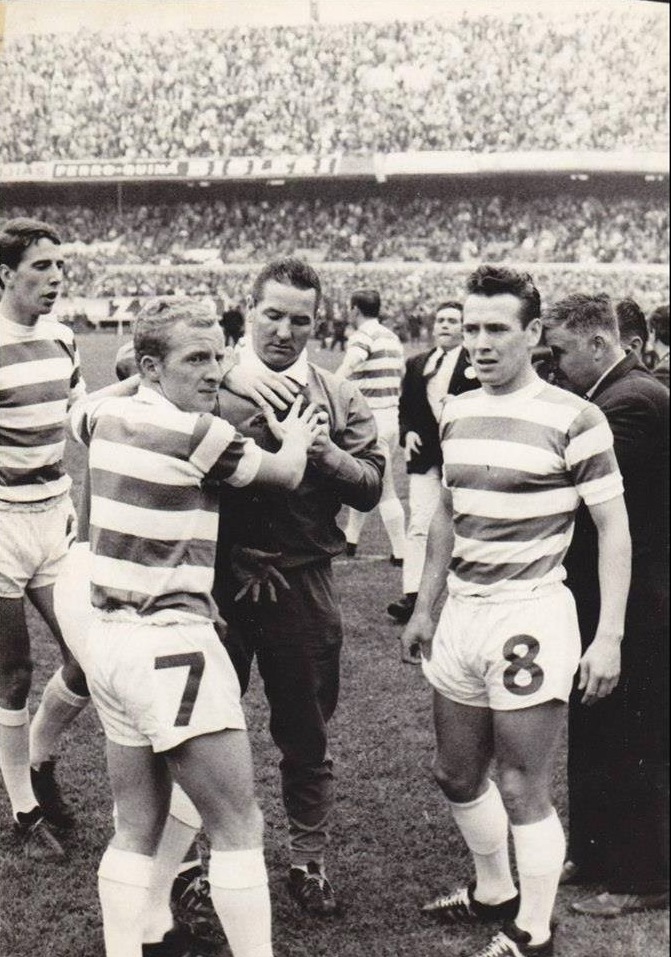

Frankly, my advice to them all is…FORGET IT! Aim as high as you like in football but don’t worry if you never get to play for that World title because then your dream might just become a nightmare – and as a Celtic player I can speak from bitter experience. We were the first British club ever to play for the Inter-Continental Cup and naturally it was a terrific honour. It was a great feeling too to be going forward as Europe’s champions, knowing that only one team stood between you and the World title.

In 1967 we thought we could win that title. We were playing good football and we were a better side than the South Americans. But that was before we knew very much about our opponents, Racing Club of Argentina. Later, we were to discover that their plans for winning the World Crown had very little to do with football.

These Argentinians were like no team I had ever encountered before. Indeed, I think it is fair to say that they were the dirtiest, most ruthless, and despicable bunch of soccer hatchet-men ever gathered together under the one set of jerseys. In all grades of football you’ll find the tough guy and the ‘fly’ man. But Racing Club were in a class of their own.

They were the masters at heel-clicking and catching you with their elbow when the ball was well away and they had long since perfected every other dirty trick known in football, including a fair amount of spitting. I’m not saying they took us by surprise. The Boss, Jock Stein, had compiled a pretty thick dossier on them before they reached Scotland and he warned us that in the first leg at Hampden they would be a certain amount of trouble, as the best way to slow any game down is to commit as many fouls as possible. We were just as determined not to let them knock us out of our stride.

The Hampden tie worked out as anticipated. They played a purely destructive game and we refused to be upset. Self-discipline was easy for us on that October evening because as far as behaviour was concerned this game was no different from any other. Every player at Parkhead knows he will get no sympathy if he is guilty of field offences. In fact, although it was well into the second half before Billy McNeill headed the winner I think we all gained confidence from this match because Racing did not appear to have much to offer in the finer points of football, although they gave us one or two hints that they knew a thing or two about unarmed combat.

It was not until the second leg in Buenos Aires, however, that we fully realised why Racing are known as the ‘dirtiest team in South America’. The astonishing thing is that their coach, Jose Pizzuti, is a most pleasant wee man off duty and was a really skilful player in his day. You would think he would seek the same kind of reputation for his team. Instead, when he went for that coaching certificate, he must have studied under SMERSH!

Ten days after the Hampden game we were flying in over the skyscrapers of Buenos Aires to prepare for the second leg. At that time we were an optimistic outfit because we sensed that the Boss believed we were capable of getting the draw, which would be enough to give us the World title. We moved out immediately to the luxurious Hindu Club and on that first Sunday we got off to a light-hearted start.

As it was a day of Obligation most of our party went off to find the nearest Catholic church. That left the Boss, Bertie Auld, Willie Wallace, Ronnie Simpson and myself. So we headed for the golf course. And what a start the Boss made. Over the first none holes he played as if he had been searching for that course all his life. No wonder all the wee local boys skipped around his heels and fought to pull his clubs. They knew class when they saw it and the Boss looked at us as if we were lucky to be playing with him. He was in a great mood and, like any golfer who thinks he has suddenly found the secret; he could hardly keep the smile off his face.

Then the bubble burst. After the turn the Boss’s ball began to go in all directions and the wee boys retreated to a safe distance. Even the smallest member of the gallery soon realized that old man Simpson, commonly known as ‘faither’, was the real golfer in the company. By the eighteenth he had the gallery to himself and the Boss was pulling his own caddie-car.

Yet I think I remember that round of golf because it was the only time during our stay in South America that I saw him looking really relaxed. Usually he hides his feelings well, especially in the tension before a big game, but he was obviously concerned about these matches with racing Club.

The strain the Boss was under would show through during training sessions. Usually, as we train, a lot of cross-talk goes on and the Boss is liable to take as much a part in it as anybody, but in those days before the tie in Buenos Aires he would turn on anyone who was capering about and tell them: ‘That’s enough. We are here to work’…or words to that effect. So we were all on our best behaviour while we stayed at the Hindu Club. Even if we thought we were good enough to get the draw, which would give us the title, we sensed it was going to be no picnic.

And when we reached the Avellanda Stadium our worst fears were justified. Even before the game started, as we loosened up and hit a few shots t goal, Ronnie Simpson suddenly staggered and put his hands to his head. He had been hit. A narrow rectangular piece of iron, about two inches long, had been thrown through the fence, which is supposed to protect the players.

Boy, were we angry! It was ridiculous that a think like that should happen to any player before such a big game. Ronnie, dazed, shocked, and obviously in pain couldn’t possibly play and it meant our reserve John Fallon suddenly found himself playing in a World tie at two minutes’ notice. At least he hardly had time to get nervous, but I could not help thinking this was one time when fate wasn’t working for Celtic.

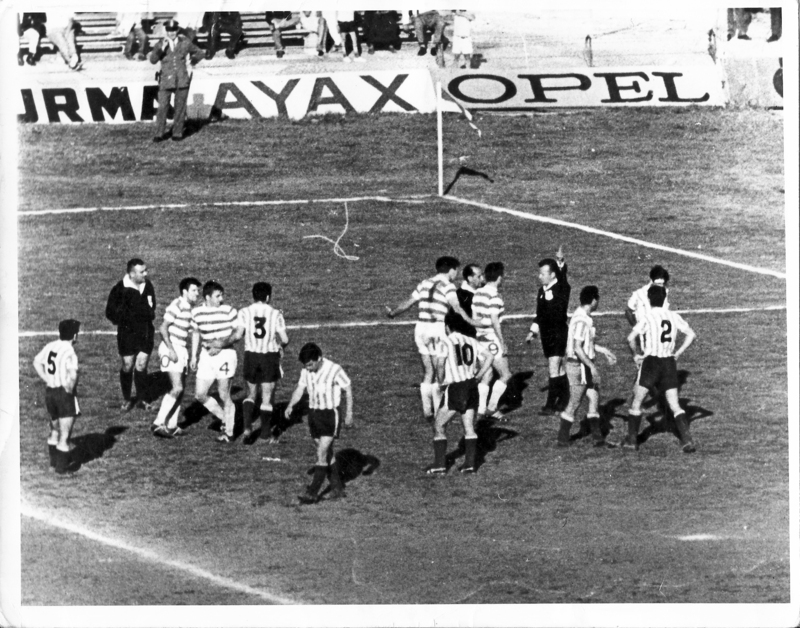

Yet despite Ronnie’s injury and despite all the unfriendly Argentinians in that stadium, we actually came very near to victory in Buenos Aires. In fact, we scored first. With what was virtually his last gesture of neutrality, the referee awarded us a penalty. I never took a kick with more determination and it was worth a guinea a box to see the expressions on the faces of racing Club. The turning point came, however, when Jimmy Johnstone scored what looked like a perfectly good second goal, only to have it chalked off. Racing equalized after that, yet at the interval we still thought we had a chance. The Boss urged us, as he had done before kick-off, not to ‘annoy’ either racing or their supporters. He couldn’t have guessed how difficult this was going to be!

For racing got their second goal soon after the interval and from there on they decided to take no chances. Their tackling became worse and worse and after a while you didn’t need to decide whether to pass or hold the ball, because if you did not get rid of it immediately, someone was sure to send you sprawling. Jimmy Johnstone suffered more than most of us, but we all had to remember, firstly, not to annoy the Argentinians.

Well, we didn’t annoy them. Instead they hacked, tripped and pushed their way to a 2-1 victory, which earned them a third-game play-off for the title, which they were obviously determined to get at all costs. We trooped back to our dressing room, disgusted. I’ll never forget it. We were so incensed at the treatment we had had to take from these South American soccer gangsters. Nobody made a dive for the bath as they would normally do. We just sat there trying to think of words bad enough to describe Racing Club who had obviously been confident the Uruguayan referee would let them away with anything.

Then we were joined in the dressing room by our own officials. Chairman Bob Kelly told us he would not allow us to play a third game against these opponents. I think that cheered most of us up because we were so fed up with the whole affair we would have like nothing better than to grab the first plane back to Glasgow.

Half an hour later we would have been happy to settle for a ‘pass out’ from that dressing room. The atmosphere had become chaotic. Argentinian and Uruguayan officials poured in when they heard we did not want to play a third in Montevideo, and they were followed by Press men, photographers, police, and anyone in Buenos Aires who had nothing better to do at the time. At least, that’s how it seemed because there was simply no room to move and most of us had still not changed.

As the flash-bulbs went off and interpreters tried to sort out the various arguments, it was difficult to know whether our next destination would be Scotland or Uruguay. At one stage the Boss asked us if we were prepared to play Racing Club again and we said ‘Yes’, mainly because we could tell from his attitude that he thought we could still win the third game if we got protection from the referee. The Uruguayans assured us the next game would be strictly controlled, and finally Mr. Kelly took their word for it.

I didn’t know then, of course, that if the Chairman had been adamant and refused to play in Montevideo I would have been spared the most embarrassing football experience of my career…but I’ll tell you about that later.

We had cheered up a lot by the time we flew out to Uruguay the next day. We had heard that the fans in Montevideo didn’t like racing Club at all and were sure to be behind us. And any doubts we may have had about this story were quickly dispelled at the airport. We got a great reception; the crowds were shouting ‘Celtic, Celtic’ and that really gave our morale a boost. It pleased us even more when we were visited at out hotel by the Penarol players, the former World Champions who had played us in a friendly at Parkhead. They confirmed that Racing Club had a reputation for being a really nasty bunch, hut they were sure we could beat them.

The Boss must have been cheered by all this too because there were two occasions when he showed how quick he can be with the gags. There was a phone call and one of the waiters in the hotel came up to him and asked: ‘Are you Stein?’ In the local accent, however, it sounded like ‘Are you stayin’? – and quick as a flash the Bog man replied: ‘No, I’m leaving on Sunday.’

Outside the hotel the following day he really had us rolling about. We had been invited to go to a nearby shop where we could get some bargains in clothes. The proprietor was delighted to see us. He wore a broad smile and, like me, he had the kind of nose, which leaves very little room for the rest of your face. “This is wonderful,’ he said. To think you come all the way from Glasgow to my shop. And you know what? I’ve got a cousin in Glasgow. Maybe you know him. His name is Levy.’

The rest of us smilingly shook our heads. Our clothier friend didn’t realise how many people there are around Glasgow with a name like Levy. But the Boss had the answer. After a moment he said ‘Levy? Sure I know him. Your cousin must be Betting Levy!’

As the rest of us nearly choked trying not to laugh, the Montevideo man could hardly contain himself. ‘Sure, sure’, he cried, ‘that sounds like him. But is he doing well?’

Back came the deadpan reply: ‘Doing well? He takes a fortune every week!’

That was the news this leading light in Montevideo Menswear had been waiting for. He could hardly serve us after that because he was obviously bursting to spread the word among his relations that their nearly forgotten cousin in Scotland was making a fortune and seemed to be a household name.

This little bit of kidding by the Boss gave the clothier a great deal of pleasure – and it helped the Celtic camp a lot too. It gave us something to look back and laugh about for the rest of the day and as the ‘decider’ approached our mood of optimism was increasing. Yet at the same time our preparations were deadly serious – so serious that Bertie Auld and I were nearly thrown out of the them altogether!

It happened like this. On the afternoon before the game Bertie and I sat in the hotel lounge chatting to some Press men. Time passed quickly and it was a long while before we realised we were the only players around. No wonder. Up in one of the rooms the Boss was holding his final tactics talk and nobody had noticed we were missing. By the time we sheepishly put our heads round the door the meeting was almost over. Later the Boss had a few things to say to both of us and he finished by telling us very frankly that if the next day’s game had been anything less important than a World tie we would have been out of the team and in the grandstand.

Since we were in we were able to join the rest of the boys in a search for a Uruguayan flag. It had been decided that since the local fans were supposed to be on our side they would back us even more if we went out with their flag. So about twenty minutes before the kick-off we all strolled on to the field, waved, acted like a most friendly bunch of fellas, then unfurled the flag. The fans seemed to like the gesture, but their response wasn’t quite as enthusiastic as we had hoped. Back in the pavilion we soon found the answer. Someone told us that ten minutes earlier the Racing Club party had been waving an even bigger Uruguayan flag than ours!

Yes, one up to the Argentinians – and a lesson to us all that no matter how smart you may think you are in these top international competitions you should always remember that the other fellow is thinking too and he may come up with an even better idea than you. It’s this kind of thing, no doubt, which puts an extra strain on managers.

Before the game the Boss warned us, as usual, of the need for self-control. He no doubt hoped, as we all did, that the assurances given about firm refereeing would keep the wild men of racing Club in check. Yet I’m sure he sensed our mood that if the South Americans kicked, hacked and spat at us any more we would do a wee bit of Scottish ‘sorting out’.

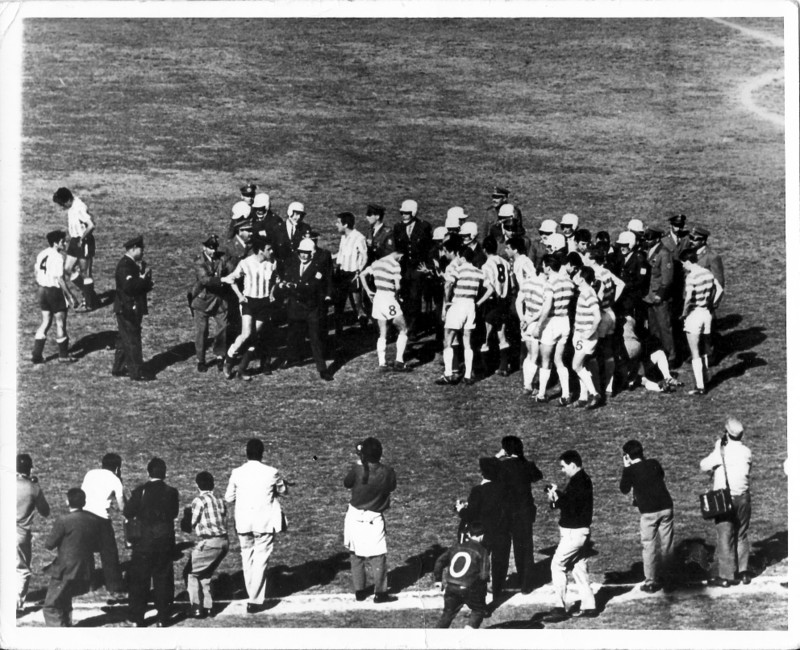

It was obvious, after hardly any time at all, that Racing had no intention of altering their tactics. Our appeals to the referee were a pure waste of time and after one particularly vicious foul on Jimmy Johnstone I think we all decided that was the last straw. I could see our blokes were no longer holding back and the game became nothing more than an exhibition of unarmed combat.

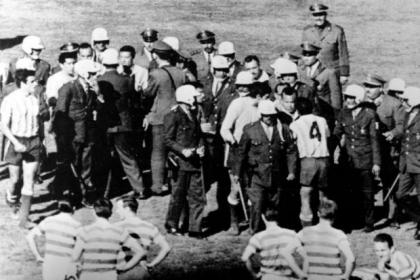

The Paraguayan referee was not slow, however, to spot crimes committed by anybody in a Celtic jersey and as the game went on John Hughes, Jimmy Johnstone and Bobby Lennox were all ordered off and Racing had the one goal lead which they no doubt felt justified all their diabolical tactics.

So, as near as I can guess, there would be about ten minutes to go when I decided that justice had to be done. After the umpteenth incident players and officials were gathered round the referee and Bertie Auld. It was all very heated and everyone was trying to see what was happening…but one player was standing apart. He was making sure he wouldn’t be involved. I wasn’t surprised because he had managed to stay out of all the real trouble throughout the tie. This was Raffo, wearing a No.11 jersey and looking quite pleased with himself. It made me so annoyed to think that the tie was nearly over and this man looked like finishing it unscathed, yet of all the members of the ruthless Racing team he had been the most consistently dirty. Yet he was crafty enough to do all his spitting and kicking when the referee was looking the other way. Nobody had been able to get their own back on him because he jumped high in the air every time you tried to tackle him. As I looked at him I thought: ‘I bet he’s thinking the Scots are a soft lot because he’s “given us stick” all that time and got away with it.’ All this had gone through my mind in a matter of seconds and in sheer temper I decided to hand out justice myself. I ran quickly round to where he was standing and kicked him. The swing was well timed, the aim was good too, and my boot landed on a very tender spot. Mr. Raffo squealed like a pig and went down in a heap. I quickly returned to my previous stance feeling very, very pleased with myself. Because of the fuss round Bertie hardly anyone had seen my little deed and it did my heart good to know that Raffo had got what was coming to him.

Now, I’m not going to defend myself. I’m not suggesting this was a nice thing to do. If another player annoys you it is no solution to kick him deliberately. But in this instance it seemed the only way to deal with him. Racing Club had set their own standards in these matches and to get down to them you had to stoop pretty low.

Mark you, I had no idea what an infamous kick that was to become. I certainly never dreamed I would have to spend days, even weeks, explaining it when I got back to Glasgow.

The trouble began when, on the Wednesday evening after we returned home from South America, the BBC showed a film taken during the game in Montevideo. I never saw it so I was completely taken by surprise when I arrived at Parkhead on the following morning and the first people I met said:

‘You’re some guy you…what a daft thing to do in front of the cameras! What a fool you are!’ And I couldn’t even start to print some of the other things, which were said to me in the days that followed.

It seemed that the BBC had managed to get hold of a film which highlighted most of the fouls committed by Celtic and somehow missed the dirty work done by the Argentinians. And I was assured that by far the most dramatic shots were of a bloke called Gemmell kicking a bloke who was standing minding his own business.

Yes, while I had been getting my revenge on Raffo a TV camera high in the stands had followed my every move. I haven’t seen that particular film yet, but I’ve been told often enough that my hasty retreat after delivering the blow did not look particularly dignified on the screen. I thought I was just helping the cause of justice… but I never thought justice would be seen to be done by about ten million British viewers, including my family and friends. I was widely criticised, of course, especially by English critics who had been waiting on an opportunity to knock Celtic. They had been shocked when we won the European cup; annoyed that we had done so much more than any of their teams.

Even my mother said to me the first time I visited her after the TV film had been shown: ‘Why did you have to go and kick that man?’ I explained, as I’ve tried to explain here, and I think she understood. Many other people still think what I did to Raffo was outrageous, but I think they will understand the atmosphere in Montevideo better when I tell this story, which has never been told before.

The fact is, the most amazing thing about that game, as far as I was concerned, happened as I was walking off the field, Raffo ran over to me… and was smiling. He made signals and at first I thought he was looking for a fight! Then I realised he wanted to swap jerseys with me. Swapping jerseys is an international football custom, of course, but you tend to do more of it in a game where relations have been good. It seemed strange to me in that situation and I admit I was suspicious. I thought: ‘ This bloke probably wants me to pull the jersey over my head so he can belt me one when I can’t see him.’

But Raffo looked so darned friendly I felt I could hardly turn him down. So I warily got out of one sleeve first, then the other, then, stepping back quickly, I whipped my jersey over my head. His smile became even broader, and as we swapped jerseys he warmly shook my hand. Indeed, as he ran towards the tunnel he had a grin on his face and, in English, he shouted a little remark about the accuracy of my kick.

In the game of football as we know it, it seems unlikely that Raffo should have anything to do with me. But at home, among my other souvenirs, I have a neatly pressed Racing Club jersey with vertical blue and white stripes and a No.11 on the back which proves that its former owner was less upset by that kick than the millions of TV fans who saw it in Britain.

Players like him kick – and expect to be kicked. It is the way some of them play the game. Referees in most European countries would not stand for that behaviour. That’s why I started off warning youngsters that playing in the World Championship is an experience they can probably do well without. I feel certain Celtic would not take part again in similar circumstances. It is a good idea that the European Champions should meet the Champions of South America each year, but these games are going to get out of control too often unless these is a neutral venue.

I would play the World final in New York. It might deprive the clubs of a financial bonanza, but if the referee was a thoroughly reliable man, carefully selected, then we could be sure the winners would be worthy champions. I certainly think no British team should ever agree to a World series in which two of the three matches could be played in South America. If the 1967 title had been decided over ninety minutes in a neutral country there is no doubt we would have been able to take it back to Parkhead.

As it was, our encounter with Racing Club brought us nothing but trouble. After we got home, and even after the TV film, another shock awaited those of us who had played in Montevideo.

One morning during training we were told the Chairman wanted to meet us at 11.30. The Boss admitted that it had to do with our behaviour in that third game in Uruguay. Celtic through the years had always had a good reputation for discipline on the field and it certainly been tarnished in Montevideo. There had to be a punishment and the Boss wanted our opinion on whether it should be spread over the entire team or merely those who had been sent off. We immediately said it should be a team affair. He had known what our answer would be anyway.

So there were eleven very shocked individuals in Parkhead that morning when Mr. Kelly announced that the Board had decided to fine each of us £250!

There were those who thought this was just a gesture to impress the public and that we would never really have to pay all that money. But they didn’t know Bob Kelly. He doesn’t do things like that – and every penny of the fine was deducted from bonuses, which we had earned previously in other matches.

Mr. Kelly was also ready, however, to accept part of the responsibility. As he announced the fines he confessed that he should have stuck to his original decision in Buenos Aires. He said he ought never to have allowed us to play in that third game and tha t he had no doubt in his own mind that he had made a mistake.

t he had no doubt in his own mind that he had made a mistake.

I think everyone would agree with him now. If we had refused to play the third game, especially after what happened to Ronnie Simpson, football people everywhere would have been on our side. Many would have regarded us as the best team in the world even if we had no official title. But it is easy to be wise after the event.

WORDS: TOMMY GEMMELL

*Extract from The Big Shot by Tommy Gemmell and first published in 1968.