TODAY CQN brings you the third EXCLUSIVE extract from Alex Gordon’s book, ‘CELTIC: The Awakening’, which was published by Mainstream in 2013.

The book covers the most amazing decade in the club’s history, the Sixties, an extraordinary period when the team were transformed from east end misfits to European masters.

AS 1960 made its debut, with the cruel wind shrieking and wailing to herald the advent, a deep depression was not setting on the east end of Glasgow. A pall of despair had already been in evidence for some considerable time. Celtic Football Club welcomed the New Year in much the same manner an over-indulging late-night reveller relished a thumping hangover.

The decade got into motion with the traditional 1 January game against Rangers at Celtic Park and, with total predictability and monotonous regularity, the Ibrox men went home with the points as they had done in their previous two league visits to the ground where once, in years gone by, they were tested to the limit. On this occasion, Frank Haffey, six foot two inches of goalkeeping enigma, offered hope with a swooping save from a Billy Little penalty-kick. It was merely a stay of execution, the sufferings of thousands temporarily held in abeyance. A last-minute goal from Jimmy Millar sent the green and white legions into a state of grief that afforded no room for the merest hint of optimism with four months of the season still to play.

The Celtic support must have been getting used to the lack of Festive Cheer in these fixtures; Rangers had triumphed in the previous five encounters and you had to go back to 1954 to discover a Celtic success when Neilly Mochan got the only goal of the game. However, the latest loss was only one of thirteen defeats from thirty-four games the club would suffer in a thoroughly miserable 1959/60 league campaign. There were nine draws and only twelve successes in an era when you got two points for a win.

Manager Jimmy McGrory saw his team finish ninth in the eighteen-club formation of the old First Division with a total of thirty-three points, failing to even achieve a point per game ratio. They had won only six of their previous eighteen outings before the New Year’s Day defeat. They were non-starters in the championship race. The club were a catastrophic twenty-one points adrift of eventual title winners Hearts. Kilmarnock (50), Rangers (42), Dundee (42), Motherwell (40), Clyde (39), Hibs (35) and Ayr United (34) could also look down on Celtic. Third bottom Airdrie were only five points away from matching the total of a team in obvious steep decline. The process of disintegration of a famous old football club was as painful as it appeared irreversible.

THE BEGINNING…Jock Stein signs as a player for Celtic, watched by manager Jimmy McGrory.

Any hopes of early season success in the League Cup were rendered redundant after the first three group ties – defeats against Raith Rovers (1-2), Partick Thistle (1-2) and Airdrie (2-4). The once-mighty, once-feared, once-powerful Celtic were being propped up mainly by their faithful support as oblivion beckoned. But even the most devoted fan was getting more than a little frustrated with the lack of fulfilment being displayed by what they perceived to be a seemingly apathetic and unambitious board of directors and a faltering football-playing staff. The resources of enthusiasm to be found in the heart of even the most fervent follower are not limitless.

Hearts and Rangers were the two best-supported teams in Scotland; drawing a remarkable 70,000 spectators to Ibrox when the Edinburgh men won 2-0 in October 1959. Celtic were a poor third, often playing in front of estimated gates of 20,000. Where some supporters swore allegiance, others simply defected. The pain of watching eleven men in green and white hoops in turmoil on a consistent basis was too much to accept for some. Only 10,000 bothered to attend a November fixture against Ayr United at Parkhead and witnessed a dismal performance in a 2-3 defeat. The alarm bells were sounding. Was anyone bothering to listen?

When Willie Fernie swept a last-minute penalty-kick beyond a static Rangers goalkeeper George Niven for the seventh goal in a momentous 7-1 League Cup Final triumph over their oldest rivals at Hampden on 19 October 1957, no-one could have predicted Celtic would have to wait another eight years before they again won meaningful silverware. From glory days to grim times was a transformation Celtic affected with a worrying ease. Those were eight long and arduous years even for the most steadfast of supports to endure.

There’s an old saying that goes along the lines of, ‘When you don’t have anything, you take what you can get’. That just about summed up the outlook of the suffering supporters who dipped into their often-meagre wages for the privilege of standing on the terracing in all sorts of conditions and watching their favourites, with uninspiring predictability, toil against even the most indifferent opposition. Three separate games against a distinctly average Partick Thistle team critically exposed the fragile state of a team in freefall.

The Firhill side eased to a 4-2 triumph at Parkhead in April for their third success over their more exalted and bigger Glasgow brother. They had also beaten Celtic 3-1 at Firhill earlier in the league and picked up another win bonus in their 2-1 League Cup victory. This, remember, was a Maryhill outfit that contrived to finish below Celtic in the league that season. There was pandemonium within Paradise as the entire club blundered and stumbled along a well-worn path strewn with mismanagement, misjudgement, miscalculations and monumental mistakes.

It was obvious to all that Jimmy McGrory was not being allowed to manage. Chairman Robert Kelly would ask McGrory to submit his team sheet at the usual Thursday night board meeting and then made what he believed to be the ‘appropriate’ adjustments. It has been said by many that McGrory was ‘too nice to be a manager’. Never once did he complain about being abruptly overruled and his decision-making questioned before being dismissed for the evening. The power that Kelly wielded over team selection was highlighted in a farcical moment in October 1960.

Bertie Auld recalled the incident. He said, ‘We were travelling on the team coach when Kelly spotted Willie Goldie, our third team goalkeeper, standing at a bus stop. He was wearing one of those old woolly Celtic scarves. That was enough for Kelly to order the driver to stop and pull in. He gestured for Willie to come onto the coach. Presumably, Willie thought he was merely getting a lift to old Broomfield where we were due to meet Airdrie.

‘John Fallon, who had played in our first four league games of the season, had been chosen to turn out again. Kelly, though, was so impressed at Goldie making his own way to the game that he immediately told him he was playing. We knew he wasn’t joking; Robert Kelly rarely did humour. Poor John Fallon! He just sat there for the remainder of the journey with a bemused look on his face after his kit had been handed to Goldie, who had to borrow boots, as well. But, remember, this was Celtic in 1960 and you came to expect the unexpected. Anything could happen. And often did.’

Alas, there is no happy ending to this tale. Willie Goldie made his first team debut for Celtic – and never played again. He dropped two clangers, Airdrie won 2-0 and his career at the club he loved ended with the final shrill of the referee’s whistle. Hilarious to some, but completely unprofessional to most. John Fallon, an innocent in all of this, also appeared to be deemed guilty for Kelly’s folly. He never played another league game during that campaign with the unpredictable and unconventional Frank Haffey coming back into the side.

The supporters craved any kind of reasonable signing during the summer of 1960. They practically begged the board to buy players of experience and substance. Celtic parted with a paltry couple of hundred pounds to sign a chunky centre-half called John Cushley from Junior club Blantyre Celtic. The player’s dad, Ned, was friendly with some of the backroom staff and had pointed them in the direction of his son. At the same time, Rangers were unveiling the elegant Jim Baxter, signed from Raith Rovers for a Scottish transfer record fee of £17,500, a colossal amount of money in those days. The Ibrox side could also afford to pay Airdrie £12,000 for their bulky central defender Doug Baillie. Back in that month of July in 1960 it was yet another indication of the gulf between the two clubs. What once was a crack was now a chasm.

An energetic teenager made his first team debut against Third Lanark in the opening game of the 1960 League Cup campaign. John Hughes netted the first of well over 100 goals for the club with veteran Neilly Mochan adding the other in a 2-0 win. It got better for Hughes, only seventeen, when he proved to be unstoppable when, against all odds, Celtic won 3-2 over Rangers at Ibrox in another League Cup-tie.

He recalled, ‘I knew I would be up against Doug Baillie who had arrived with a big reputation in the summer. That meant little to me, to be honest. I had been scoring goals for Shotts Bon Accord only the previous year and I thought I could continue to do the same with Celtic. I enjoyed scoring a goal in that game. It was a wonderful experience.’

The Glasgow Herald were suitably impressed by the powerfully-built centre-forward. ‘Celtic have produced, almost from the playground, one big fellow of great potential. Hughes, who is only seventeen-years-old, caused havoc in the Rangers defence even when, for the greater part of the second-half he was the only Celtic forward in position to threaten Rangers’ goal, so committed to defence were his colleagues. The even bigger, heavier Doug Baillie, the home centre-half, was time and again confused as his much more nimble opponent beat him for speed and for control of the ball.’

Hughes was sensational in the opening ties, but, when it mattered most, Celtic faltered. They lost their last two qualifying games and Rangers, after a 2-1 win at Parkhead, qualified to eventually go through to the final and claim the trophy with a 2-0 triumph over Kilmarnock at Hampden. Jimmy Millar, only 5ft 7in but an exceptionally aggressive centre-forward, often terrorised the Celtic defence in those days. He once admitted, ‘My fellow forwards, players such as Ian McMillan, Willie Henderson and Ralph Brand, never really wanted to get involved in the more physical stuff, so I took on that role. Some might say I was a better boxer than footballer.’ Billy McNeill probably agreed.

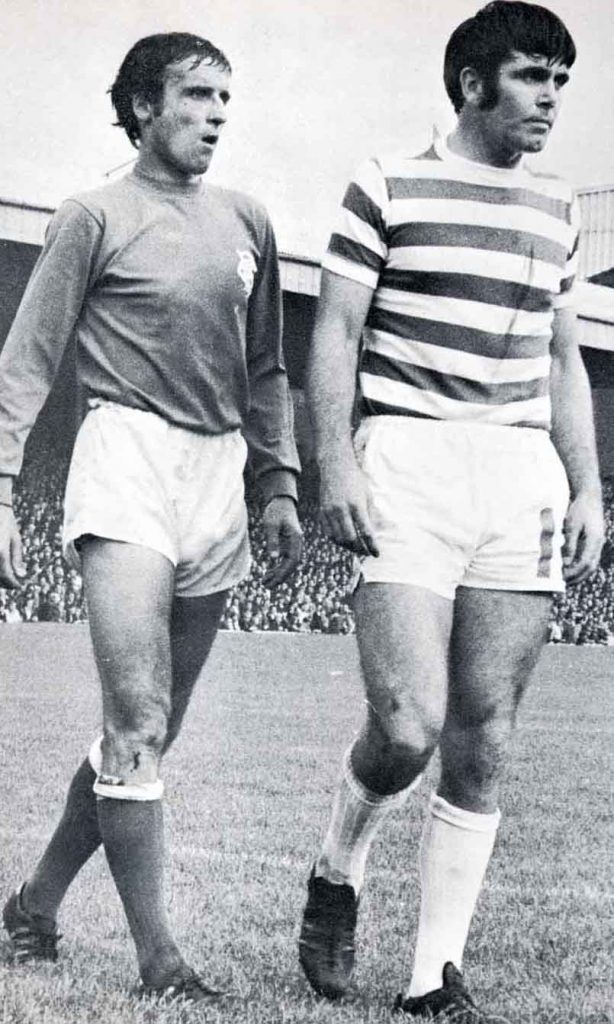

BIG YOGI ON THE PROWL…John Hughes, known to the Celtic support as ‘Yogi Bear’, is watched closely by Rangers centre-half Ronnie McKinnon.

However, in the search for positives, the performances of the giant John Hughes had stirred the Celtic support. Five goals in six games was a more than decent introduction to the top side, particularly when you consider the lack of guidance or leadership that was denied Hughes when he joined in October 1959. ‘It was a nightmare. I was there as a big, raw laddie and, basically, you didn’t get any help at all,’ he revealed.

”I made lots of mistakes and no-one said anything. Players at the age of seventeen are commonplace these days, of course, but back in 1960 it wasn’t the case. Most teenagers were waifs and needed built up. I was playing centre-forward in a bad Celtic team and scored thirty-one goals in my second season. I got 113 in my first five years. I often feel that if I had been given some advice in the early years I would have been a far better player. I was told I was inconsistent and a lot of that was because of the fact no-one was saying, “You’ll need to work on that” or “How about trying it this way?” That didn’t happen. You were just told to get out there and get on with it. There was little or no help offered. Believe me, I would have welcomed advice and I would have acted upon it. But none was forthcoming.’

For whatever reason, and you are invited to draw your own conclusions, John Hughes sat out the whole of October and November, missing eight games, before returning to score Celtic’s goal in the 1-1 draw with Dundee United at Parkhead on 10 December. Despite that, he wasn’t required for first team duty for the remaining three fixtures of 1960. At least, Hughes could console himself, at the age of seventeen, he had reached double figures for appearances, ten in all, with six goals thrown in.

The two youngsters who were thought most likely to make the grade were wingers Matt McVitie, signed from Wishaw Juniors, and Jim Conway, who arrived from Coltness United. McVitie turned out thirty-four times and scored ten goals, one of them in a rare Scottish Cup win against Rangers in 1959, and Conway netted nine times from thirty-two outings. McVitie was seventeen-years-old when he made his league debut against Rangers in the New Year’s Day game in 1958 that resulted in a 1-0 loss.

He left in November 1959 for English lower league outfit Cambridge Town. Bertie Auld remembers him as being ‘a frail lad’. Conway was also seventeen when he took his top team bow in the opening league game of the 1957/58 season, a 1-0 win over Falkirk. Apparently, he grew disenchanted with life at Celtic while attracting the attention of a certain Jock Stein, manager of Dunfermline at the time. The possibility of a move to Fife didn’t materialise and the player signed for Norwich City in 1961 for a reported fee of £10,000, a bid Celtic would have found impossible to resist.

However, the latter half of 1960 had been good for one prospect in the shape of John Hughes, raw and ready to go. The New Year’s Day fixture against Rangers was now just around the corner. Could Celtic hurl themselves into 1961 with a long-overdue victory and avenge six consecutive and painful reversals in this historic fixture? A crowd of 79,000 was at Ibrox Stadium to find out.

* TOMORROW: JOCK v CELTIC: Part four of CQN’s EXCLUSIVE extracts from Alex Gordon’s book ‘CELTIC: The Awakening’ which takes an in-depth look at the club in the defining decade of the sixties.