TODAY CQN brings you the fifth EXCLUSIVE extract from Alex Gordon’s book, ‘CELTIC: The Awakening’, which was published by Mainstream in 2013.

The book covers the most amazing decade in the club’s history, the Sixties, an extraordinary period when the team were transformed from east end misfits to European masters.

THE Celtic fans did not have to suffer the pain and humiliation of a seventh consecutive New Year’s Day defeat from Rangers in 1962, the annual ritual no-one of the green and white persuasion anticipated with any particular fondness. Winter’s icy grip, unforgiving and unremitting, obliterated fixture lists throughout the country with pitches all over the place being deemed unplayable.

These were the freezing old days before the advent of undersoil heating and, back then, the ground staff at Parkhead would spread bales of hay on the surface days before the game and then attempt to brush the frost-covered straw off the pitch as close to kick-off time as possible. This action, of course, served to confuse player and fan alike when the markings on the pitch were fairly well disguised. There was also the use of braziers, strategically appointed around the playing area. This equipment was not the most imaginative, innovative or workable of ideas as they often scorched the grass directly beneath them. So, on this occasion, the conditions were the winners and the Celtic support, for the first time in seven years, weren’t forced to endure a different kind of Ne’erday hangover.

Celtic had waved a fond farewell to 1961 with a 4-0 success over Raith Rovers two days before Christmas Day. Would 1962 eventually be ushered in with another victory? Alas, no. Kilmarnock were the visitors to Parkhead on 6 January once the snows had cleared and the thaws had made known their welcome presence. It was a lively encounter, but Celtic and their fans had to settle for a 2-2 draw with Stevie Chalmers and Bobby Carroll pulling the trigger for the Glasgow side.

MASTER MARKSMAN…Stevie Chalmers.

Four days later Chalmers, with his ninth goal of the league campaign, was on target again, but once more it ended in stalemate against Third Lanark. Chalmers was a likeable guy off the field, but on it he was a demon, no goalkeeper was safe when Stevie was around. If they fumbled a shot or a header they knew there was every likelihood he would be on to it in a flash, taking ball and keeper into the net if need be. The player’s route to a career in the hoops was a strange one. He started at Junior side Kirkintilloch Rob Roy, moved to Newmarket Town and then on to Ashfield before being spotted by Celtic at the age of twenty-three.

He would often shake his head in disbelief and say, ‘You know, I signed for Celtic from Ashfield on 6 February 1959 and made my debut just a month later against Airdrie at Celtic Park. Unfortunately, we lost 2-1, but imagine that – one month I was turning out in Junior football and the next I was playing for the famous Glasgow Celtic. Couldn’t happen today, could it? Possibly not surprisingly, that was my only appearance of that particular campaign. Now you see me, now you don’t! But I realised I had been handed a great opportunity by Celtic and I wasn’t about to pass it up. I knew I could score goals for this club.’

Meanwhile, it had been awhile since the chants from the away fans of ‘Ha Ha Haffey’ had been heard, but, as anticipated, it was only a matter of time before his alter-ego put in an appearance. Big Frank was at his butter-fingered worst as Dundee United lashed four behind him at Tannadice on 13 January, but, fortunately, he was bailed out by the blokes in front of him. Mike Jackson (2), John Hughes (2) and Pat Crerand were among his rescue party in a rollercoaster ninety minutes. Jackson said, ‘You never knew what you were going to get with Frank. He looked a world-beater on occasion and then performed like a rookie in the next game. In fact, if you were really unlucky, you would get both in the one game. It couldn’t have done much for the nerves of our defenders.’

FIVE OF THE BEST…Pat Crerand, Billy McNeill, Mike Jackson, Jim Kennedy and Dunky McKay involved in a five-a-sides tournament in Falkirk in the early sixties.

Undoubtedly, Johnny Divers, like Jackson, should have thrived under the influence of Jock Stein. One of his admirers was teenager John Hughes. He said, ‘I thought Johnny was a very under-rated player. He helped me a lot when I first came into the team and he was only a youngster at the time, too. As Mike Jackson points out, he scored over one hundred goals for the club and he was an inside-forward and not a main striker. That’s a fabulous total, but he, too, was moved on when Jock decided it was time for him to go. Like so many before him, he could have contributed so much more and his name should have been in lights.’

Bobby Lennox made his debut against championship-chasing Dundee in March at Parkhead in front of a crowd of just over 37,000, the majority of whom would go home happy after Celtic’s 2-1 victory. Lennox didn’t mark his baptism with a goal, but he would make up for it as his career unfolded; 273 times, to be precise. So, that was one game down and 570 to go for the man who would become known as ‘The Buzz Bomb’. Admittedly, the Dundee team that visited Glasgow that day had lost a little of their verve and venom while the talismanic Alan Gilzean toiled with injury problems, but they were still a formidable outfit and they had their eyes on winning the title for the first time in the club’s history.

Frank Brogan, a speed merchant on either wing who had been signed from St.Roch’s the previous year, got Celtic’s first goal and once again you are left to ask the inevitable question: What on earth happened to him? Brogan, whose brother Jim would later play for Celtic, looked the real deal with pace to burn, an eye for goal and breathtaking accuracy with crossballs while running full pelt. His style was hardly complicated. He knew he could skin any full-back with his breathtaking acceleration and didn’t over-indulge in the fancy footwork. Step-overs and the like were not for him simply because he didn’t require trickery to leave his opponent in his slip stream.

Why, then, did he falter and be allowed to leave Parkhead a year later for Ipswich Town after a total of only forty-eight appearances? Had the Celtic system failed him, too? Something, somewhere was not right because Frank Brogan possessed awesome potential and he should have been around for years to entertain the home support and terrify the opposition. Celtic’s winning goal against the Tayside men was provided by Billy McNeill with an unstoppable header from a well-flighted corner-kick from the aforementioned Brogan.

It would be extremely difficult to comprehend what happened next. Celtic were derailed again while facing another club in the relegation dogfight. This time it was Airdrie, who, at the end of the season, just escaped the drop on goal average. Two of the Broomfield side’s points total came at Celtic’s expense in a startling 1-0 win. Not for this first time, the Celtic support was left aghast at what it had just witnessed. A strong and purposeful Dundee team with their eye on the title had been beaten in the previous league encounter and here was the same side in green and white being turned over by a bunch of stragglers at the other end of the table. It was becoming increasingly perplexing.

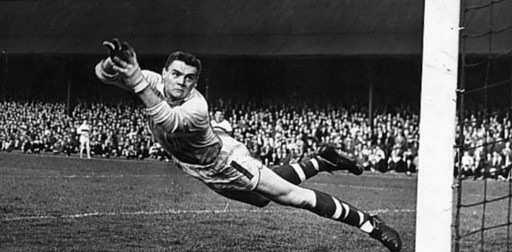

HE FLIES THROUGH THE AIR…the much-maligned Frank Haffey.

One of the reasons for the Airdrie collapse, alas, was Frank Haffey, so often the whipping boy, but, at the same time, so often guilty as charged. And this time his own team-mates turned on him following an unforgivable howler. It was comic cuts stuff as he practically threw the ball into his own net and the players converged on their embarrassed No.1 without any attempt to disguise their disgust in front of the Broomfield audience. It’s harsh to single out an individual in what is essentially a team game, but there are occasions when you can quite easily detect the turning point in a game as well as a season. Any chance Celtic had of being crowned First Division champions disappeared that day in March with seven games still to play. Deservedly, the title eventually went to Dundee.

The Scottish Cup ended in utter and unexpected embarrassment for Celtic when fans rioted at Ibrox during a 3-1 defeat from St.Mirren in the semi-final. The club had gone into the game on the back of an overwhelming five-goal success over the same opponents only the previous week. Aspirations were high of a second successive Cup Final appearance and, hopefully, better fortune than that enjoyed against Dunfermline. Rangers were due to face Motherwell in the other semi-final at Hampden the same day hence Celtic playing at the home of their great rivals. The failure of the team against an ordinary Saints outfit was as horrendous as it was unacceptable.

After the first forty-five minutes, Celtic players sought the refuge of the dressing room after capitulating three times without reply. It was too much for some undesirables with eighteen minutes left to play. Suddenly there was a pitch invasion, the players were ushered off, bottles were thrown and police were wrestling with hooligans. Unfortunately, a fringe element followed Celtic – other clubs, too, had their own problems – and their insane reactions marked a new low in times back then. The game was eventually completed and finished 3-1 with Alec Byrne pulling one back.

However, the sickening images of so-called fans swarming all over the pitch appeared in newspapers the following day and the Celtic hierarchy, as you might expect, were mortified. The club strenuously warned against any repeat. A statement read, ‘If the thugs who profess to support Celtic think that they can influence the result of a match by such behaviour they indulged in on Saturday, they are very far and dreadfully mistaken. As soon as they tried to influence the outcome of the match we, as Celtic directors, decided the match was St.Mirren’s.’

The 1961/62 season had delivered little; the league blown with seven games still to play, an inability to qualify from a League Cup section that saw a relegated side, St.Johnstone, get through and a Scottish Cup adventure that ended in chaotic scenes at Ibrox. That powderkeg situation should have awakened a few at Parkhead; the natives were getting restless. During the season they had seen their favourites written off after one particularly dull game described in a national newspaper as being ‘the worst entertainment in the east end’.

That seemed harsh criticism because, appealing or appalling, the individuals in the green and white hoops had, in fact, always attempted to uphold the traditions of the club. It’s just that they did not possess the quality to deliver to a trophy-winning standard. There appeared to be very little happening on the player recruitment front in the summer of 1962. Disconcertingly, a general apathy seemed to be settling on the club. Indeed, it would be October before money was spent in the transfer market with a twenty-seven-year-old journeyman called Bobby Craig arriving from Blackburn Rovers for something in the region of £10,000. Apparently he had also played for Third Lanark and Sheffield Wednesday, but the question asked most by the man in the Jungle was, ‘Bobby Who?’ And yet, for all the wrong reasons, his name would be on every Celtic supporter’s lips by the end of the 1962/63 campaign.

Most of the usual suspects were in place when the new season kicked off with a League Cup-tie against Hearts at Parkhead in August. Frank Haffey was in goal with Dunky McKay and Jim Kennedy remaining at full-back. The wing-halves on either side of Billy McNeill were Pat Crerand and Billy Price. John Hughes, of whom big things were expected now he was being recognised as a first team regular, spearheaded the attack and Charlie Gallagher, Crerand’s cousin, would be playing immediately in front of him in the inside-right position with Bobby Murdoch occupying the same role on the left. Bobby Lennox was fielded on the right wing with Alec Byrne on the opposite flank.

There were still no real tactics in what appeared to be a rigid 2-3-5 formation. Improvisation among the players was a luxury denied them. There would have been apoplexy in the dug-out if say, for instance, Lennox, without prior permission, wanted to swap wings with Byrne for a spell to freshen things up. And God help the full-back who wanted to cross the halfway line, a doctrine which stifled the aggressive McKay, but probably suited the more pedestrian Kennedy. Things would change. Eventually.

CAPTAIN AND LEADER…Billy McNeill.

Billy McNeill looked back, ‘We knew we had good players and we kicked off every campaign wondering if this was going to be the breakthrough season. We always wanted to make an early impact in the League Cup, but had failed to do so for too many years. It was the first piece of silverware up for grabs and we all realised the confidence that would come our way if we could win the trophy before the turn of the year. It would have given everyone, player and fan alike, a real lift. I recall we started that term with a 3-1 victory over a strong Hearts side who could prove troublesome to anyone on their day. Our failure to display any sort of consistency was evident in the next game when we lost 1-0 at Dundee. One minute we were up; the next we were down. To be perfectly honest, it was infuriating. Hearts ended with eight points to our seven and that was the end of the League Cup for another year. I have to admit to feeling a fair degree of sympathy for John Hughes. He had scored thirteen goals in the competition since making his debut against Third Lanark three years earlier and had yet to play outside the group stages.’

Rangers travelled across Glasgow for the first Old Firm encounter of the season. Once more the litmus test had arrived so early. The Ibrox side were still smarting after being dismissed by Dundee in the previous season’s race for the flag and had made all sorts of threats and promises throughout the summer. It was crunch time for them, too. Could they deliver? Manager Scot Symon had his strongest team at his disposal and, unfortunately, they answered the rallying call with Willie Henderson, a darting imp of an outside-right, beating Haffey for the game’s only goal. Consistency and this set of Celtic players were never bedfellows. The league had barely started, the players still sporting their summer suntans, and already Celtic were playing catch-up. Unfortunately, it was so typical of the times.

Both Old Firm clubs have always shown a ‘nosey neighbour’ interest in what is happening and what is going on in each other’s camps. The public mantra is quite different, of course, but it’s a lot of hogwash. If someone sneezes at Parkhead then they want to know about it at Ibrox. And vice versa. So, what had been happening across the Clyde during Celtic’s abysmal run? Rangers, in fact, were undefeated on their own soil and had dropped only two points out of ten. You can win championships with form like that. While Rangers dazzled, Celtic, sadly, dithered.

Muhammad Ali and George Foreman did not invent the Rumble in the Jungle in Kinshasa, Zaire, in 1974 as anyone who was in the vicinity of Parkhead to watch the early season 1-0 defeat from Queen of the South would surely testify. Clearly, the dreadful inconsistency of the team was more than just merely irritating the Celtic faithful. It had now reached the level of unsettling a support that felt the need to let its feelings known.

The club sailed serenely on, hitting every iceberg that was possible. Robert Kelly and his fellow board members were regular targets for some vicious verbal abuse as tempers frayed and snapped on the terracing. Jimmy McGrory, it appeared, was immune from criticism, the supporters having too much respect for a club legend. Alas, for the chairman and his directors, they didn’t fall into that category, as far as the fans were concerned.

After the Queen of the South catastrophe, Celtic went on a run of five games without success. The club had barely reached December and any thoughts of unfurling a championship flag at the start of the next season had been shredded and binned. It was like being forced to watch rerun after rerun of the worst movie you had ever seen. In slow motion. There was no escape and, yet, emotional ties brought the man with the bunnet back every matchday, the proverbial moth to a flame; the glutton for punishment.

The league was out with their reach, but there was no way they would allow Rangers to saunter to the title. The Celtic players readied themselves for beginning the dismantling job on their old rivals on the first day of 1963.

* TOMORROW: STUFF OF NIGHTMARES: Part Five of CQN’s EXCLUSIVE extracts from Alex Gordon’s book, ‘CELTIC: The Awakening’, an in-depth look at the most fascinating decade in the club’s history, the remarkable sixties.