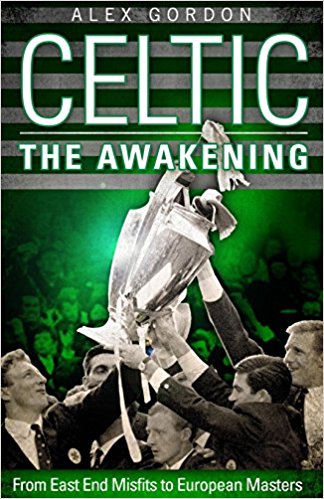

TODAY CQN brings you the second EXCLUSIVE extract from Alex Gordon’s book, ‘CELTIC: The Awakening’, which was published by Mainstream in 2013.

The book covers the most amazing decade in the club’s history, the Sixties, an extraordinary period when the team were transformed from east end misfits to European masters.

BILLY McNEILL and Bertie Auld hadn’t even notched up one hundred appearances between them when they prepared to embark on their wondrous football odyssey. McNeill, at the age of nineteen, had played thirty-three first team games with twenty-one-year-old Auld turning out in sixty-two. They were in at the start and completion of Celtic’s remarkable sixties; the only two players to do so. The journey into the seventies was just as exhilarating and memorable. Both have extraordinary tales to tell about the turnaround in the club’s fortunes. Here they talk to the author about their experiences.

ALEX GORDON: Could either of you have foreseen the revolution that was around the corner when you played and lost in the 1960 New Year’s Day game against Rangers?

BILLY McNEILL: There was no leadership and it was obvious mistakes were being made at the club, but we lived in hope. Remember, we weren’t just Celtic players, we were fans, too. The club meant everything to us and, although we weren’t getting much joy on the field, we still wore that jersey with pride. If the supporters were hurting, you better believe we were, also.

BERTIE AULD: Yes, these were obviously frustrating times for everyone connected with the club. There seemed no rhyme or reason to a lot of the decision-making. For instance, I had hoped to play against Rangers in the League Cup Final in 1957, but I was dropped and missed the 7-1 victory. I had played in six successive ties leading up to the final and had scored three goals, too. But, without a hint of explanation, I was dropped from the Hampden squad. There was no man-management. I was out and no-one bothered to sit down with me and discuss the situation. I was only nineteen-years-old at the time and, naturally, I was bitterly disappointed to miss the big game. You might have thought, after playing in the previous six ties, I might have at least got a seat in the stand. No chance. I was packed off to play for the reserves against Queen of the South in Dumfries. Mind you, Neilly Mochan came in, had a stormer, scored two goals and we gubbed them, so there were no complaints afterwards. However, even today, it is difficult to comprehend that I could be transferred in 1961, have four years at Birmingham City, and return to Parkhead and the club still hadn’t won a solitary trophy in that period. You didn’t expect such a barren run at a club like Celtic.

McNEILL: The club should never have allowed Jock Stein to leave in 1960. That was a huge error of judgement on someone’s part. Jock was in charge of the reserves and the players really enjoyed working with him. Not once did I hear anyone question his methods. I’m not being wise after the event because I said it back then. Jock was always going to be a huge success as a manager. He was light years ahead of his time. I was close to Jock, of course. I suppose he could have been seen as a bit of a mentor. I think it helped that he had played in my position at centre-half and could work on that and pass on his knowledge to me.

AULD: Everybody on the playing staff admired Big Jock for his football knowledge. Even experienced first team players, guys who had played alongside him, listened when he spoke. He was immersed in the game and very enthusiastic. He thought about it constantly, even down to the most minute of details. Jock would work on free-kicks, corner-kicks, even throw-ins. Everyone knew what was expected of them when he was in charge. He was always on the ball and never missed a trick. He realised he had a dressing room full of Celtic fans. If the guys he brought into the club weren’t Celtic fans, it didn’t take them too long before they would become one. The supporters won’t know this, but when they were singing their songs out on the terracings before a game, the players were singing them, too, in the dressing room. When they put the music on the tannoy and gave it pelters with ‘Hail! Hail! The Celts Are Here,’ we were giving it big licks as we prepared to go out on the pitch. Jock made sure our dressing room window was always open on matchday. It was high up near the ceiling and the fans couldn’t see through the frosted glass. It didn’t matter if it was sub-zero temperatures, that window remained open. As the supporters made their way along Kerrydale Street and were bashing out their songs, we were listening to every word and singing along with them. Without realising it at the time, it was a fabulous bonding experience between the players and the man on the terracing.

BHOY WHO WOULD BE KING…a youthful Billy McNeill.

McNEILL: Jock was a great seeker of knowledge. He would travel all over the place taking in games and, more often than not, paying out the cash from his own pocket. I know he went to Wembley in 1953 to watch the Hungarians play against England. They were the emerging nation and Jock wanted to see them for himself. Nowadays, you can flick a switch and get games beamed into your living room from anywhere in the world. Obviously, that wasn’t the case back then. Jock watched a team that possessed the great Ferenc Puskas take England apart, winning 6-3. The English still thought they were the best in the world, so a result like that really shook up football. Jock must have taken a lot of notes that day. He noticed that Hungary deployed their centre-forward Nandor Hidegkuti in a deep-lying role and England didn’t know how to react to this tactic. Jock was so impressed that he bought one of those old-fashioned movie projectors, probably state of the art back then, obtained film of the entire ninety minutes and pored over it time and again at home. God knows how many tapes of that Wembley game he must have wiped out!

AULD: That was the man’s style, Billy. He could take in a top-flight international one night and then pop into watch a Junior game a couple of days later. He always insisted you would pick up something from every game if you watched properly and concentrated. By the way, I have to say the English goalkeeper that day against the Hungarians knew his football. It was Gil Merrick who signed me for Birmingham City!

GORDON: How popular was Jock with the players?

McNEILL: I know I was seen as his blue-eyed boy, but that was never the case, believe me. Possibly because I was captain, he rarely gave me a doing in front of my colleagues in the dressing room. But I knew what to expect afterwards when he said, ‘Billy, can I have a word?’ Then he would let me know what he thought of my performance. I think if you gave him 100 per cent all the time and cared deeply about the club, he was a great ally. If you stepped out of line, he was down on you like a pile of bricks.

AULD: Jock never courted popularity among the players. He never saw that as being part as his remit for the job. All he ever wanted to do was get the best for Celtic. He treated individuals in different ways. There were some who would sulk and retreat if he gave them a verbal blast. However, he would know these characters would respond better to an arm around their shoulder and a quiet word in their ear. He was full of surprises, though. I recall a game I had against Rangers in a Glasgow Cup-tie at Ibrox in 1966. I had a stinker. Virtually nothing I tried that night came off. After the match, he came over and congratulated me for a pass I had hit that set up a goal for Bobby Lennox. I was expecting a hammering. Mind you, it probably helped that we won 4-0!

GORDON: How did it feel making the breakthrough to the first team back then?

McNEILL: Nerve-wracking! No, I just went out to do my absolute best in every game. I knew what the Celtic supporters looked for in a player. They wouldn’t accept someone they spotted not giving it their all – and you can be sure they would clock a player not performing at his utmost. I think they made allowances for young lads such as myself and gave us great encouragement. Their backing at such a crucial stage in the club’s history was absolutely vital. Even when we weren’t playing too well, and that was the case for far too long, we were still getting crowds of 20,000 to 30,000. That was an awful lot of people making an effort to get along to Parkhead on matchday to see a team they probably knew beforehand might not excel. But they still turned up, thankfully.

AULD: In those days, the players could actually socialise with the fans. There weren’t the huge barriers there are today where the gulf between the working man and the present-day player is widening by the minute. They are not on the same planet these days. I loved the rapport with those supporters. Still do. They knew their football, that’s for sure. No-one talked down to them. If they had a grievance they knew they could talk to you about it. They could sidle up to you in the pub and have a word. Big Jock constantly drummed into us that these guys were the lifeblood of football and deserved to be entertained. ‘Football without fans is nothing,’ he would often say. He was right, too.

McNEILL: Although Celtic hadn’t been too successful in picking up any silverware, they still tried to put on a show for the man on the terracing. The team had a lot of colourful characters the fans could identify with. Those personalities played in what became known as the Celtic Way. It may not have brought in the trophies, but it was certainly watchable. We scored a lot of goals. Mind you, we shipped in a few, too!

DETERMINED…Bertie Auld shows the steely expression that guided Celtic through a large part of the sixties.

AULD: Billy, I can remember a funny story when you were beginning to make an impact in the reserves and were looking at breaking into the first team. Bobby Evans, who became a great friend of mine, used to pick me up after training in the afternoon and give me a lift in his car to Glasgow city centre. A few other team-mates – guys such as Paddy Crerand and Mike Jackson – would catch a lift, too. We would congregate in an Italian restaurant called Ferrari’s in Sauchiehall Street and we would talk non-stop about football. Bobby would drop us off and then drive onto his newsagent’s shop elsewhere in the city where he would put in a shift there until closing time around 6pm. Could you believe that? He was the captain of Celtic and Scotland and there he was selling newspapers and cigarettes to the punters! Do you know, no-one thought that unusual back then? Today’s players don’t know they’re born. The point of the story, though, is that Bobby was a wee bit anxious about your arrival. You were getting noticed in the reserves and he knew you were a centre-half and that was his position. He had played in the old right-half berth earlier in his career because he was such a fine passer of the ball and he also had a good engine. But he had settled in at No.5 and he enjoyed playing in central defence. However, there was a young whippersnapper on the scene and he was under pressure.

McNEILL: If I remember correctly, I was pushing for a first team place at the start of the 1958/59 season, but Bobby, who I must say was always an inspiration to any budding centre-half, played in the first league game against Clyde. Celtic lost 2-1 at Shawfield.

AULD: I recall that game, Billy, because I scored our goal. However, to be honest, we didn’t play well that day.

McNEILL: Ironically, we played Clyde three days later in the League Cup at our place and a few changes were made to the line-up. I made my debut and I was in at centre-half and Bobby was left out. We won 2-0 and I believe you scored again. We had already beaten them 4-1 at Shawfield in the opening game in the tournament. Do I remember you scoring that day, too, Bertie?

AULD: As a matter of fact, I did score in both those games. I had no idea I was such a goal machine!

McNEILL: We were due to play Rangers at Celtic Park in the league at the start of September and I wondered if I would be selected again. Obviously, I really wanted to play in that one, but no-one could have blamed anyone if Celtic had gone for experience and reinstated Bobby. I was only eighteen-years-old at the time, after all. However, I was delighted to keep my place and we drew 2-2.

AULD: I didn’t score in that one, Billy. My wee pals Eric Smith and Bobby Collins were the men on target that day. ‘The Wee Barra’, as Bobby was known, was a fabulous player. He was a real dynamo. Bobby made me feel so welcome at Celtic right from the start. I remember him giving me his Adidas boots from the 1958 World Cup Finals. They were slightly big for him – his feet were tiny – but they were my first major manufacturer’s pair. I had been making do with all sorts of inferior models until then. I was the envy of all the younger players at the club. I thought it was a marvellous gesture and he was a major influence on me. He realised the reserves of today were the first team players of tomorrow.

McNEILL: Bobby was a great source of inspiration to us all, Bertie, as we were coming through. Unfortunately, I didn’t get much time with him in the first team because he moved to Everton that season. Bobby Evans also left for Chelsea. That was a pity because you can learn so much from such individuals.

AULD: I know I did. The Wee Barra was a winner. He was physical and a bit robust, but he was not a dirty player. And when you were struggling in a game or made a mistake he would be the first to offer alternatives. You could not help but admire him.

McNEILL: Like I said earlier, we might not have won too much during that period, but we did have some wonderful individuals. There was ‘The Wee Barra’ and Bobby Evans, for a start, but there were others such as Charlie Tully, Willie Fernie, Neilly Mochan, Bertie Peacock and yourself, Bertie. Goodness knows how a team with that sort of talent didn’t wipe the floor with their opponents. That will remain a mystery forever.

AULD: Well, we didn’t have much direction, Billy. We had precious little tactics, if any. If someone had taken more time in training to work with us things could have been a whole lot different. I’m sure of that. For instance, I came into the team as an outside-left and God forbid if I ever came in from the wing. My job was to get down the flank, fire over crosses and leave it to others to try to put the ball in the net. Any sort of improvisation was frowned upon.

McNEILL: That’s right. The defenders were there to defend, the midfielders, known as half-backs, were there to run, fetch and pass, the wingers were there to put over crosses and the central forwards were there to score goals. There was precious little variation in our play. Everyone knew how we would line up and our style of play.

GORDON: Who was to blame?

McNEILL: It would be impossible to lay the blame at any individual’s door. Clearly, that wouldn’t be fair. Jimmy McGrory was the manager and he was a lovely man; a true Celtic legend as a player. But a manager back then wasn’t really the team boss. Others would have the final say in team selection and suchlike. Jimmy McGrory would be asked to do all sorts of tasks, taking care of players’ wages, match tickets and other menial duties. We never saw him during training. I never saw him in a tracksuit. He was always immaculately attired and spent all of his time in his office no doubt carrying out all sorts of duties that should have been left to other people. We were so naive back then.

AULD: I agree with you. Jimmy McGrory was a wonderful, warm man, but he wasn’t cut out for management and I don’t mean to be disrespectful when I say that. Simply put, he was from another era. It was the same across the road at Rangers. Their manager was Scot Symon and no-one ever saw him in a tracksuit. Big Jock changed everything. I recall Hal Stewart, the Morton chairman, saying something along the lines of, ‘We were all getting along fine until that upstart Stein came on the scene!’ I know he was only joking – in fact, he and Jock were big pals – but I think that just about sums up the situation in a nutshell. Big Jock came into football management with the force of a hurricane. Cobwebs were blown away at Celtic, training changed dramatically, innovative tactics suddenly came into play and we started to perform in a different manner. Others were forced to follow.

THE LEADER…Billy McNeill emerges from the Parkhead tunnel.

McNEILL: His motto was ‘Play to your strengths and disguise your weaknesses’. Simple enough advice, but, then, Jock never complicated anything. He never once asked a player to do something that was outwith his capabilities. There was no use asking me to play at centre-forward, for instance. He never put John Clark at outside-right. He knew the strengths of individuals and he instinctively knew how to get the absolute best out of them. We had flair players such as Jimmy Johnstone and sometimes Jock would let him off the leash. Jinky had all the ability in the world – I know what he did to our defence in training! Jock would see him taking the mickey, sticking the ball through your legs for the umpteenth time, and he would bellow from the touchline, ‘Right, Johnstone, that’s enough of that!’ Thanks, Boss.

AULD: Aye, Wee Jinky was a genius, but he did sometimes overlook the fact that training was for all of us. Maybe we should just have given him a ball to himself and everyone could have got on with taking care of business. We used to play a little training game when you could only take three touches before passing the ball on. Jinky would prefer to play about and maybe take some extra touches. Jock would spot this. I think we ended up playing two-touch football just to make sure Jinky would release the ball at some stage. I loved the Wee Man; he was special.

McNEILL: You can say that again, Bertie. Remember the day he threw his shirt at Jock when he substituted him in a game against Dundee United? Jinky wasn’t too pleased at having to go off early and, with that hair-trigger temperament of his, actually chucked his jersey at the dug-out on his way up the tunnel. Big Jock’s limp meant he wasn’t the quickest on his feet, but he moved that day. He raced after Jinky who later told me, ‘Billy, I thought about running straight through the main gates and heading for Parkhead Cross. I was sure Jock was going to stiffen me. I locked myself in a room and he was banging on the door. “Johnstone, get out here!” Eventually, I said, “I’ll open the door, Boss, if you promise not to hit me.” Everything went silent and then I could hear that unmistakeable shuffle of his feet as he headed back to the dug-out. I swear I could hear him laughing!’

AULD: I remember the first time I saw Jinky. This wee lad with the big red curls turned up one day for training. I thought he might be a fan. There wasn’t an awful lot of him at the time – a wee, frail figure. He sat in the dressing room and said nothing. He actually looked to be somewhat embarrassed to be mixing with some of the players. Well, that was until he got onto the pitch and then we all knew who Jimmy Johnstone was. What a talent. He was like a rubber ball. Defenders would bowl him over and he would just keep bouncing back to his feet. You could see the fear in the eyes of our opponents when they looked at the Wee Man when he started to make a name for himself. That fear was a real compliment to Jinky. There was no disguising it, either. Those opponents knew they were in for a torrid time.

McNEILL: Wee Jimmy left us with so many good memories and you could talk about him forever and a day. Actually, I believe we are so fortunate that there is so much wonderful footage of the Wee Man in action during his playing days. Film has captured all those marvellous images of Jinky doing what he did best – entertaining the fans. Those supporters were always so important to him. He loved it when they sang, ‘Jimmy Johnstone on the wing’ and he would just keep playing away, ensuring they didn’t stop! When people who haven’t been fortunate enough to witness the Wee Man playing in the flesh see film of him in action they will understand why so many folk raved about him. Jinky was a Celtic man – that’s the beginning and end of the story. He was a genuine working-class hero and I don’t think for a second he would mind me making that observation. Like I said earlier about a lot of the players back then, he was a Celtic fan who played for Celtic. He was one of the lads and success and adulation never went to the Wee Man’s head. Do you know he was actually a ball boy at the club when he was a kid? Jinky played in an era where there were an awful lot of skilful players, talented individuals and remarkable characters. But Jimmy Johnstone was the king of them all.

THE BOSS AND THE PLAYMAKER…Jock Stein with Bertie Auld following the goalless draw against Dukla Prague in 1967.

AULD: Tommy Gemmell’s got a great story about the Wee Man no-one has heard before. Jinky was as proud as punch when he bought his first Jaguar car. We all got a chance to walk round it, look inside – ‘That’s real leather, no’ any yer plastic!’ – and he loved to drive it all over the place. One day, he and Big Tommy were going for a wee bit of fishing and he picked up TG before heading off for some place in Perth. Tommy was giving Jinky instructions and at one point said, ‘Straight through the roundabout, Wee Man.’ Jinky took it literally, drove up through all the flowers and stuff and came down the other end! ‘Fuck’s sake, Wee Man!’ shouted Tommy. ‘Well, you said straight through,’ answered Jinky. You had to watch when he was around. I thought it was fitting that the supporters should vote him The Greatest-Ever Celtic Player in their millennium poll. Do you know he was surprised? He thought the award would go to Henrik Larsson. So typical of the Wee Man.

GORDON: We discuss the European games, the world club championship Final and other situations elsewhere in the book. So, going back to the beginning, what was it like in those Old Firm games when Rangers were undoubtedly top dogs?

McNEILL: We realised these games meant so much to our supporters and we all felt as though we had let them down when we didn’t produce a good result. To be fair, they had a very good team back then with some very useful players. You didn’t have to look at anyone else other than Jim Baxter to see the class players they had at their disposal. I got on well with Jim and he, myself, Paddy Crerand and Mike Jackson were great mates off the park. The Rangers hierarchy frowned on one of their employees associating with Celtic players, but Slim Jim didn’t give a stuff. He liked our company and that was the end of it. On the park, though, he was immense. That left foot of his could open up any defence. Mike Jackson recalls a great story about Jim no-one would have believed. Certainly, it couldn’t happen today. Jim had been out for a wee drink with some of the Celtic players before an Old Firm Glasgow Cup-tie which was due to take place the following evening. Now, as we all know, Jim liked a beverage and slightly overdid it that particular afternoon that followed into evening. Eventually, Jim got a bit tipsy. No-one had a spare bed, so Mike took the Rangers player to his mother’s place in Govanhill where he crashed out on the sofa in the living room. Now Mike’s mother just happened to be very religious and the frontroom was packed with holy pictures and statues. Jim must have wondered where on earth he was when he came to! Actually, religion never came into it when Jim was mixing in our company. On the day of the Glasgow Cup game, he got cleaned up, got a bite to eat and Mike came over to pick him up on a taxi to take him over to the game. As my pal recalls it, Jim had a blinder that evening against Celtic. Only Slim Jim could get away with that.

AULD: Jim was only at Rangers a matter of months when I returned from Birmingham City in 1965. Just as well for him or we would have seen who had the better left foot! Only joking, the lad could play all right. He came back from England, after spells with Sunderland and Nottingham Forest, in 1969 and the only time we were ever in opposition was a League Cup-tie at Ibrox. I got on as a substitute that night, but we lost 2-1. The newspapers raved about Jim’s return the following day. However, we turned the tables and beat them 1-0 at Parkhead to get through eventually to the final where I scored the only goal to beat St.Johnstone 1-0. So, I never really got the opportunity to pit my wits against Slim Jim. I would have looked forward to it, let me assure you.

McNEILL: Some of the results in the early sixties were difficult to accept. The 3-0 defeat in the Scottish Cup Final replay against Rangers in 1963 is still one that rankles. We had played well enough to get a 1-1 draw in the first game, but, unaccountably, we just didn’t turn up four days later. We were two goals down early on and, sad to say, it was game over. Jim was exceptional that evening. We never got to grips with him and the match just passed us by. That was a sore one. It’s hard to believe, but three of that team – myself, Bobby Murdoch and Stevie Chalmers – would win European Cup Final medals four years and ten days later. We would have had you certified if you had predicted that in the Hampden dressing room that night!

AULD: I loved Old Firm occasions. I was confident enough to believe we could win every one of these games, even when we were struggling. Some players don’t want to know in these games and they’re quickly found out. They are so intent on not making a mistake that they don’t produce anything worthwhile. The ball is passed around like a live hand grenade; they can’t get rid of it quickly enough. There was a fair bit of banter between the players before these confrontations. John Greig was talking to me in the tunnel one day and said, ‘Bertie, we’re picking up £60-per-week at Rangers these days. What are you on at Celtic?’ I replied, ‘Just a little bit short of that, John, but, then, we get win bonuses and you don’t!’ Then we would go out and kick lumps out of each other. I revelled in the tension, the electric atmosphere, the tribal rivalry between both sets of supporters; och, the lot. Mind you, it was even better when we won. It would be fair to say I enjoyed these occasions a lot more in the second half of the sixties than I did at the start!

GORDON: You kicked off the decade with a defeat against Rangers and completed the ten years with an 8-1 victory over Partick Thistle. Does that just about sum up the see-saw sixties?

McNEILL: It would have been difficult to envisage us having a seven-goal winning margin in the early period. As I’ve said, we were more than capable of sticking the ball in the opposition’s net, but they scored against us, too, with far too much regularity. In my first twelve league games of season 1958/59 we netted twenty-six goals which is a fair ratio. Balancing that, though, we conceded twenty-three. We scored three against Falkirk at Parkhead and lost four. We got three against St.Mirren and they got three against us. Hibs, at Easter Road, were another team to hit three into our net as they beat us by the odd goal in five. I missed a game against Stirling Albion in Glasgow when the lads up front did the business, scoring seven. Our keeper Dick Beattie conceded three, though. I think early on I realised that life was never going to be dull at Celtic! But those scorelines at the start and end of the decade do emphasise a shift in how we played. We could still attack, but now we knew we could defend, too. It took us awhile to get the balance right, but we got there in the end.

AULD: Spot on, Billy. During your debut season I got well into double figures in goals which wasn’t bad for a guy who was supposed to be stuck out on the left wing. But the opposition certainly knew the route to our goal. We had players in the team back then who never helped out in defence. Charlie Tully was a special talent, a real maverick, but I don’t recall him doing too much back-tracking. He always wanted the ball at his feet and he would go off on a mazy dribble. That was his forte; heading balls off his own goal-line clearly wasn’t! The team always seemed better geared to attack and shutting the back door wasn’t a priority. That was Celtic’s style, though. It was drummed into us to put on a show for the fans. It appeared we were entertainers first and foremost and professional footballers second. I can tell you the board back then didn’t even like you going in hard on the opposing players. Our directors had an almost puritanical approach to football. God help you if you actually injured an opponent. Your ‘reward’ would probably be a lengthy spell in the stand. Jock changed that outlook, too. If the ball was there to be won, he expected you to win it. He was never specific on how he wanted you to go about winning the tackle, he just expected you to emerge with the ball. ‘Win the battle and you’ll win the war,’ was another of his favourite sayings. Thankfully, we did that more often than not during his reign.

GORDON: It’s been a pleasure talking to you, fellas. Thanks for the memories, Billy and Bertie.

McNEILL: I’m always happy to talk about the good, old days. They bring back so many wonderful memories. The fans, too, deserve massive credit for the way they stuck by the team. Certainly, I’ll never forget the way they treated me. It may have been a bit rocky at some points, but, hopefully, we gave them some memorable moments along the way. I know they gave me plenty.

AULD: Aye, those supporters are brilliant; they’re the best in the world. No matter where I go, I tell everyone that. When things weren’t going too well, they were our twelfth man. Those fans were our substitute before substitutes were allowed in football. You might have been struggling in some games, toiling to get things going and then suddenly you would hear ‘Hail! Hail!’, look up at the terracing, see those magnificent fans and then the adrenalin was pumping again. How could you let down those guys? Great days shared with great people.

* TOMORROW: PARADISE LOST: Don’t miss the third EXCLUSIVE extract from Alex Gordon’s book, ‘CELTIC: The Awakening’, published by Mainstream in 2013.