As I pressed the security buzzer, I felt a sense of excitement and trepidation at what lay beyond those vast Lennoxtown gates. A group of fellow supporters patiently bared the open expanses outside as they gripped on to prized tops, balls and photographs, eagerly anticipating a glimpse of one of their Hoops’ heroes. As much as I wanted to, I would not be asking for autographs once I made it inside; my first visit to Celtic’s modern training facility was on account of an interview I had arranged the previous week and I aimed to maintain a level-headed sense of quasi-professionalism.

“Who is your appointment with Mr Dykes?” echoed the polite query from the security box.

“Danny McGrain,” came my almost disbelieving response.

The gates slowly opened as if I had exclaimed those immortal words of admission, “open sesame.” I tried to comprehend the gravity of the two infinitely more sublime words I had just muttered as I drove slowly towards the main building to meet a living Celtic icon.

20 minutes early, I was asked to sit in the reception area, which caused me no displeasure as Neil Lennon’s first-team were in the throes of a bounce match just beyond a glass panel. Sitting in my imagined sky box, I was enthralled by the skill of the enigmatic Samaras; amazed at the tiny frame of Robbie Keane; and amused by Artur Boruc, who had assumed the position of centre-forward on account of a broken finger sustained in the midweek win over Rangers.

“Paul John?,” was the call from above that aroused me from my transfixed gaze. As I looked up the stairwell, Danny McGrain looked back down on me like the messiah himself, holding a bundle of passports in each hand. “I’m running a wee bit late, can you give me five minutes?” My immediate nod of affirmation did little to disguise the fact that I had waited 31 years for this moment and another five minutes was not about to throw me off the scent.

Once inside Chris McCart’s office, which overlooked the inside training pitches below, I wondered how many of the names on the wall-mounted white board would ever become modern-day Quality Street Kids. It was a term I had first heard on Celtic’s centenary history video many years before. The tape arrived for Christmas 1988 and I always wondered what became of The Quality Street Gang. The last bastion of world class talent to emerge from Barrowfield entered the room and my quest to find out began.

“The young boys are going to a tournament in Hong Kong and I’m trying to make sure they’re all organised,” Danny explained as I shook the hand of a man I had idolised through the pages of The Celtic View, Shoot, Match and Roy of the Rovers since the early 80s. Back then, Celtic reared their own. It was a tradition that bore the sweetest fruit in the 60s and 70s as Jock Stein’s side blazed a trail around Europe and transformed Celtic into the worldwide phenomenon they were to become. Somewhere along the way, the vision was lost and the myopic insistence to change the formula resulted in a dearth of homegrown talent that lasted years. Now on his own emissary to nurture the next generation of Quality Street Kids, Danny and I discussed his own development into one of the most respected full-backs in world football.

Danny McGrain had signed for Celtic a couple of weeks before the European Cup final in 1967. He had been playing for Queen’s Park Strollers when the Glasgow side discovered him and he was taken to Casale Monferrato in Italy the following year to participate in the under-21 international youth tournament that was dubbed by the Daily Record as the ‘Junior European Cup’. McGrain, who was a versatile performer who could slot in at full-back or in midfield, looked back on the birth of a career that was to span two trophy-laden decades:

“Tommy Reilly brought Sean (Fallon) to Ibrox when I played for Scotland under-18s against England,” he said. “We got hammered and it was a horrible winter’s day. The ground was heavy and the English guys were just giants running about in the mud. I remember being carried off at the end with cramp in both my legs. I played left-midfield then, left-half, and Ibrox is a big park for any 16-year-old so I was running around chasing people and chasing the ball. There were a lot of scouts there and I was getting carried off, and I thought, ‘I’ve blown my chances of playing for Celtic.’ But Sean Fallon phoned my mum and said, ‘Can I come up and see Danny about signing for us?’ And he came up to my house in Drumchapel in 1967, it was before the European Cup final although I don’t remember watching the game and thinking, ‘That guy was in my house’.”

For years the young Danny McGrain has been described as a ‘self-confessed’ Rangers supporter. It is a ‘fact’ that has caused much annoyance to fans of the Ibrox club who could not fail to be impressed by his world-class performances at full-back for Celtic and Scotland throughout a remarkable career. This dismay was further compounded when it was discovered too late that McGrain could have played for Rangers despite their never-admitted signing policy being imperiously potent in the late 60s and throughout his playing career. McGrain dismissed the myth that his heart ever belonged to the other side of Glasgow as he explained, “We weren’t Rangers supporters or Celtic supporters. When I was 16 or 17, I didn’t support a team because I was too busy playing for my school team in the morning and Queen’s Park in the afternoon. My dad was never a supporter of any club and funnily enough, in the whole street in Drumchapel, I don’t remember any time there being fights through Celtic or Rangers winning or losing. I don’t remember any of that happening. I don’t remember ever hearing or seeing anything destructive.”

So with Celtic’s inclusive approach to signing players allowing them to recruit any promising individual that happened to catch their eye, the door was well and truly open for Daniel Fergus McGrain to sign on at Celtic and the Scottish schoolboy cap was not going to let such a golden opportunity slip through his fingers. He recalled: “No one from Drumchapel made it as a professional so I wasn’t even thinking of being a football player. You were either going to be working in John Brown’s shipyard in Clydebank, as an electrician or a plumber or whatever, or you were on the dole. My dad was an electrician. My mum and dad worked, looked after themselves and brought their family up. I was on a milk run every morning for about five years, up at four o’ clock in the morning, back at eight, and then I’d go to school and play two games of football every day.

“We played football every day. Everybody played football, good, bad or indifferent. You’d play in the playground and you’d come home from school and end up playing in the back garden. There were six flats in a tenement and there was a big garden in the back, usually muddy and full of rubbish. Nine times out of ten you’d try and play out the back but someone’s washing would be out and you’d be told not to play so we’d end up playing in the street. Everybody played in the street and the goals were the lamp-post and the pavement. Obviously there were fewer cars than there are now. It was about 25-a-side and the goals would be about five miles apart. You’d play until you were hungry and then you’d go home for your tea. I must have been about 13 or 14 then.”

McGrain may have played further up the field prior to signing on at Celtic but by the time he had embarked on his first European trip away with the club he had been transformed into a full-back, equally effective on either side of the defence. Jock Stein had become an expert at identifying a player’s best position and he had already started to employ his own brand of alchemy on this special group of youngsters. “That was our first trip abroad,” said McGrain, “and I always remember the photograph being taken. I’ve got a copy of it and we’re all standing there with our blazers on. The blazers are just like cardboard, just cut. We’re all standing in a file and it would have been the first blazer we’ve all had, particularly a Celtic one. When I was shown that photograph years later I thought, ‘Look at us all with the hair all combed and we’re all shiny white and there’s not a crease in the blazer. Everyone’s just perfect’. And we were all proud to be part of this club – the European Cup winners. It was so good to be part of it at 17-years-old. I don’t think I’d ever been in a plane up until then.

“I was full-time and we had the older members who were maybe 18 or 19, players like Davie Hay, George Connelly and John Murray. I can’t remember much about the trip. I just remember it was so warm and you were playing against Italian teams and they were just flying by you because they were used to the conditions, the hard-baked ground and the heat. I’ve wondered if Mr. Stein sent us there to see how European football was being played and to take something from that, whether it was their pace or their touch on the ball. It was a great tournament to go to for us all, although some people took nothing from it. Mr. Stein was the type of person who wouldn’t tell you all the time because that was just the way he worked. If he had to tell you two or three times he would think he was wasting his time. You had to go and learn yourself. Maybe that’s why a few of us turned out to be half-decent players.”

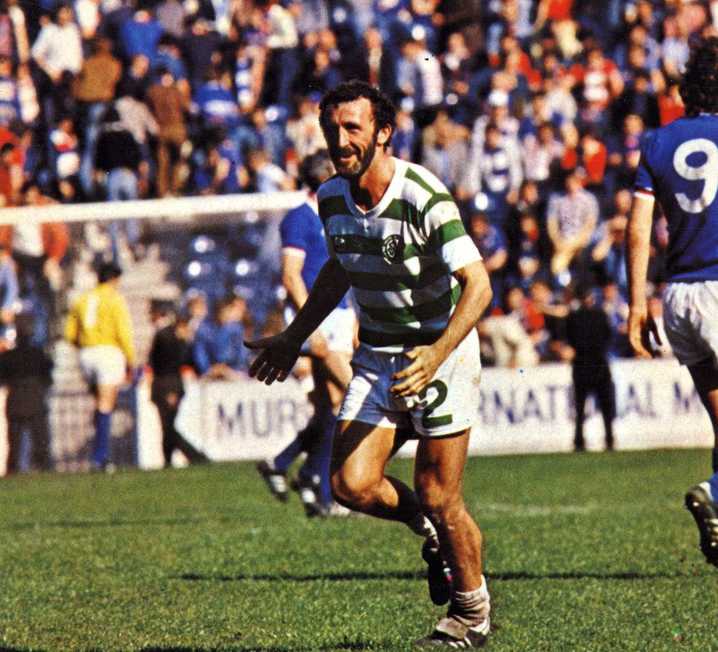

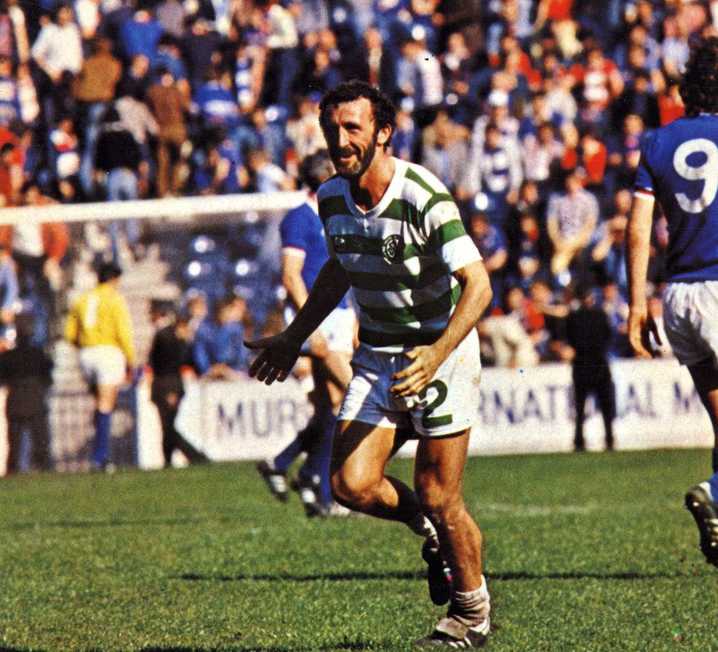

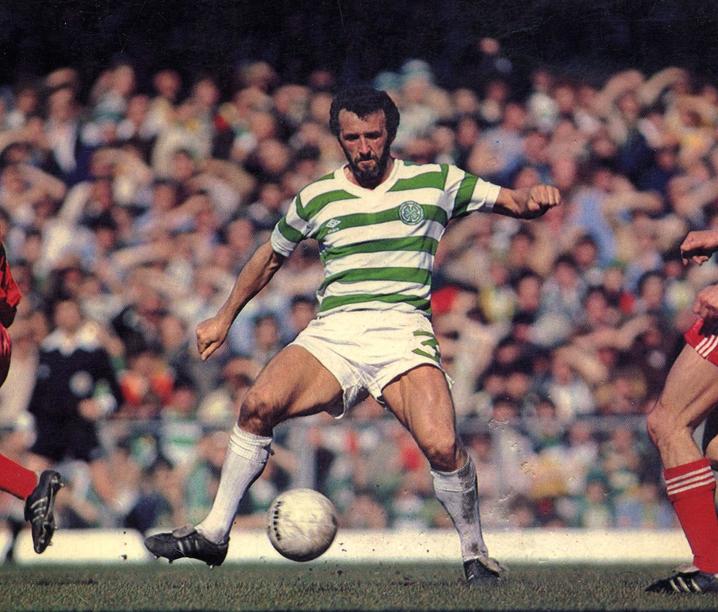

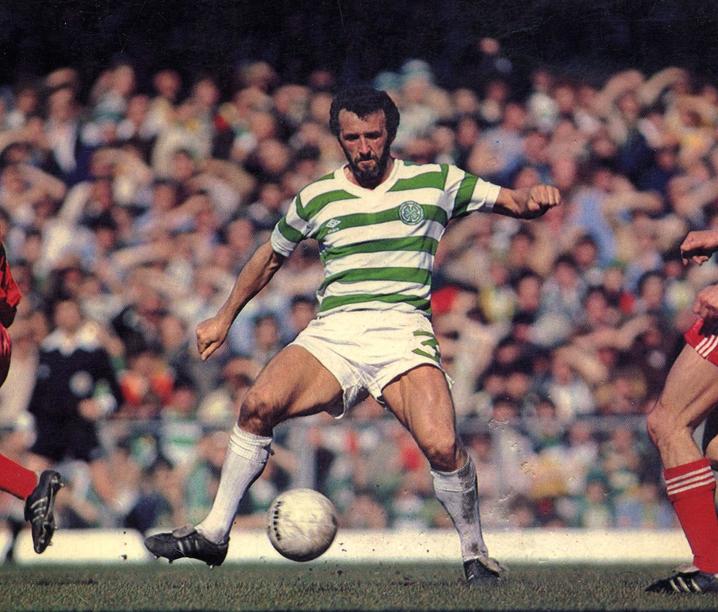

Danny McGrain proved himself to be far more than a half-decent player. Few of his contemporaries or students of the game would argue that, at his peak, he was a truly world class talent. His maiden journey beyond British shores was to become the first of many as trips abroad became a regular feature for club and country throughout a stunning 20-year career. The loyalty displayed during his time as a player at Celtic Park surely marks him out as the nonpareil Quality Street Kid.

More than three years after meeting the Celtic great, Danny McGrain gazed out at me from a cornucopia of daily tabloids holding a copy of The Quality Street Gang. The morning papers, usually the printed provocateurs, offered an unusual escape from my otherwise suburban antipathy on Thursday 10th October 2013. Here was Danny alongside Davie Hay at Celtic Park, where they had attended the previous day’s press call for the launch of my debut book. “Playing in that team with players such as Davie Hay, George Connelly and Kenny Dalglish, I was just very thankful that I was involved in it,” explained Danny. “We were the start of a very good team. At the time it was very nerve-racking. I remember we used to train up here at Celtic Park and our warm up was four laps of the park. I was at the back of the group with Kenny. We would be 16 or 17 and big Billy McNeill was at the front. We had watched the European Cup final and now we were running around the track with this squad because everybody trained together. Wee Jimmy was there and after the first lap you’re thinking, ‘when am I going to wake up?’ It was just so surreal and those players took us into their fold and wrapped a big blanket over us and from then on they looked after us for the next two or three years.

“Kenny and I and some of the young boys were still a bit in awe to ask them for advice. We just trained with them and wee Bertie, Jim Craig, Billy McNeill and Bobby Murdoch would talk to you about the family and everything else and you got to know them better. You watched them in training and what a great bunch of guys they were. I unknowingly picked up tips from Jim Craig and Tommy Gemmell. At that time I was a left-midfield player and then I grew into a full-back. I also watched Bobby Murdoch, Jimmy Johnstone, Bertie, all the guys and some of the stuff just stuck to me. It was so enjoyable. We never actually thought, ‘I’m going to make it,’ we were just happy to be here. There was a whole family atmosphere as soon as you walked in the door.

“I enjoyed playing with wee Jimmy when we used to train with the first team. I wasn’t a full-back at the time thankfully but you’d play against wee Jimmy and it was just a nightmare. I hated playing against him because he always roasted me. I’d be 17 or 18 at the time and I was stupid enough to try to kick him. Sometimes he was unlucky and I caught him but he just got up, rubbed your head and got on with it. Again that was teaching me not to be so stupid and tackle people of his ability. Bobby Lennox’s pace made me realise that I had to stand off him. I was learning these things without actually knowing it. After training and playing with these guys and listening to Billy McNeill ordering people about in training and talking to them, you start to take it all in. Looking back today I’m so appreciative of what these players did. They weren’t trying to teach us anything, they were just doing their natural thing and I learnt so much from them as did Kenny, Vic Davidson and Paul Wilson.

“I think the fact that I came through with Kenny and he got into the first team maybe a year before me and became established gave me some satisfaction. To know that Kenny was playing upfront and we had an understanding with each other maybe made me feel more comfortable. I think playing with Kenny over the years that he was here was terrific for me.”

A fractured skull, a long-term ankle injury and a diagnosis of diabetes would have cut short the careers of many lesser beings yet this outstanding footballer played in two World Cup finals and would have played in more had it not been for his injuries. His class as a player is undisputed and he also carried on these standards in the way he conducted himself off the field of play, particularly in adversity. Danny McGrain is respected by everyone who has ever met the man. He had a season in the red and white hoops of Hamilton but his heart will always belong to Paradise.

Written by Paul Dykes for CQN. To order a signed copy of Paul’s brilliant book, The Quality Street Gang visit CQNBookstore.com HERE or click on the image below.