CQN continues its enthralling and EXCLUSIVE extracts from Alex Gordon’s book, ‘That Season In Paradise’, which takes us through the months that were the most momentous in Celtic’s proud history.

Today, we look at another dramatic step along the team’s destination towards never-ending glory.

THE record books will show that the earliest big-hitting Tommy Gemmell ever scored a goal was in the twenty-eighth second. Unhappily, there was no cause for celebration because the landmark strike came against Celtic. The maverick left-back somehow contrived to slice a clearance beyond Ronnie Simpson to hand Queen’s Park a goal of a start in the Scottish Cup quarter-final at Parkhead a mere three days after the jubilation of the European triumph over Vojvodina Novi Sad.

The breezy individual can look back now on the effort that silenced the large majority of the 43,000 Parkhead crowd for all the wrong reasons and smile. ‘Sean Connery, old 007 himself, was introduced to the players before the game and then we all went out to get some photographs taken at the trackside before the kick-off. We all knew James Bond had a ‘licence to kill’, so I thought I would award myself a ‘licence to thrill’ and help our amateur opponents to make a game of it.

‘Aye, that will be right! Faither gave me an earful and I knew I had to atone as swiftly as possible. Thankfully, I got that chance only six minutes later when we were awarded a penalty-kick. Even then, the ball hit the underside of the bar before flying into the net. Now, if I had missed the spot-kick questions might have been asked.’

With the unintentional assistance of the extrovert defender, the Hampden side had become the third team to score three goals against Celtic at home that season at that stage, matching Dunfermline’s haul in the League Cup in September and Stirling Albion’s tally in the league in November. The Fifers conceded six and the Annfield side were hit for seven. Queen’s Park did marginally better and lost five. Stevie Chalmers put the Cup favourites ahead in the twenty-third minute, but the valiant opponents stunned the home support again eight minutes later when Niall Hopper equalised.

A two-goal salvo before half-time from Willie Wallace and Bobby Murdoch made it 4-2, but the Spiders outrageously claimed a third forty seconds after the interval with Hopper again on target. It was left to the ever-willing Bobby Lennox to see off the impudent Mount Florida outfit with a fifth goal six minutes from the end.

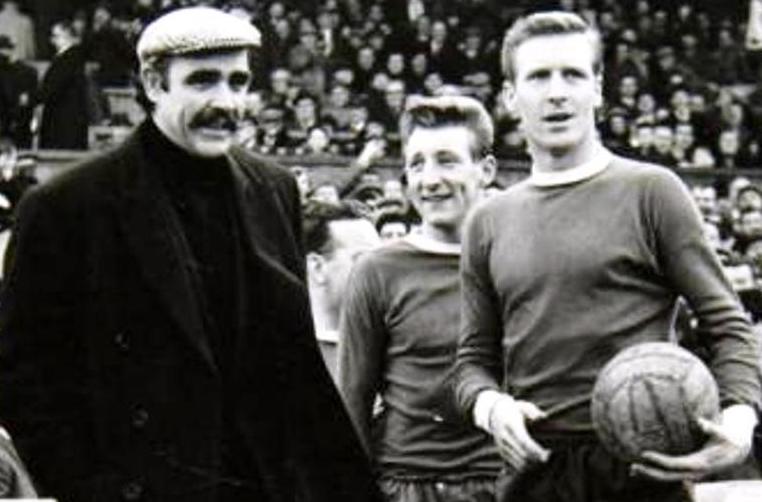

LICENCE TO THRILL…actor Sean Connery, the movie world’s 007 spy James Bond, shows his balls skills with the Celtic players before the Scottish Cup-tie against Queen’s Park at Parkhead.

The drama didn’t conclude with Lennox’s strike, unfortunately. Jimmy Johnstone got himself involved in an unseemly brawl with defender Miller Hay and both combatants were fortunate to remain on the pitch with an extremely lenient referee Jim Callaghan content to brandish only yellow cards, possibly taking into account the game had merely seconds to go until he blew for time-up. Johnstone’s misbehaviour didn’t escape the notice of chairman Bob Kelly or his unimpressed boardroom members watching the action from the directors’ box. Jock Stein may have changed their outmoded attitude towards vigorous tackling, but he was helpless to save his wee winger from punishment on this occasion.

Gemmell recalled, ‘We all realised Jinky had a temper – must have had something to do with red hair – and he just lost the plot against the Queen’s Park player. As I recall, it hadn’t been a particularly dirty game. Something, however, caused my wee pal to blow a fuse. The incident happened over at the Jungle down at the corner flag, so I didn’t get a good view. But I have to say it did look as though Jinky had demonstrated the well-known art of what is quaintly known as ‘The Glasgow Kiss’. Or, put another way, he stuck the heid on him. I think Jinky got a punch in the face in retribution, but we all thought that was the end of it at the final whistle. We could have guessed something was wrong when Big Jock told Jinky to remain behind after we had all changed, cleaned up and prepared to leave. The grim look on the manager’s face told us the Wee Man was in trouble.’

The Celtic directors hastily convened a meeting in the boardroom and, after short deliberation, Johnstone was informed the club would not tolerate such unacceptable misbehaviour by one of their players and he would be suspended forthwith for a week. The player might have considered himself fortunate. Before the influence of Stein, the board might have been persuaded to lobby for public flogging to be reintroduced. Johnstone was forced to pull out of the Scottish League squad that was due to play their English counterparts – dodging a 3-0 defeat while doing so – and the league game a week later against Dunfermline. The old Celtic board, though, weren’t so engulfed in morals as to prevent Johnstone training every day with the first team.

Jock Stein handed Johnstone’s No.7 shorts to John Hughes, but, sending out mixed signals to Dunfermline, he ordered Yogi to hug the left touchline. Once again, the ploy worked with the sturdy raider spending an enjoyable afternoon terrorising the Fife club’s right-back Willie Cunningham. In only three minutes, Stevie Chalmers took off on a spectacular horizontal dive to get his head to a Willie Wallace left-wing cross and divert the ball past his former team-mate Bent Martin low at his left-hand post. Alex Ferguson levelled matters in the nineteenth minute, but Tommy Gemmell sent an eruption of a penalty-kick high past Martin to restore the lead. Wallace nodded in the third before half-time and Ferguson, with the praiseworthy attribute of never giving up, handed his side faint hope with a second goal three minutes from the end.

Celtic, though, refused to surrender a third and the points were in the bag. Just as well because Rangers beat Ayr United 4-1 at Somerset Park on the same afternoon to go top of the table on the slenderest of goal average margins. However, the champions had a game in hand and no-one at Parkhead was pushing the panic button, but their age-old foes were refusing to give them any breathing space in a fairly anxious race for the title. It had all the indications of going all the way to the wire.

A crowd of 41,000 was in attendance to take in the encounter against Dunfermline and, incredibly, it meant the champions had been watched by over one million spectators at Celtic Park that season.

Following the triumph, one national newspaper reporter informed his readers, ‘The more I see of Celtic these days, the stronger becomes the impression that the strain of chasing domestic and European honours is having its effect. Certainly, against Queen’s Park the previous week and again on this occasion, when they played their fiftieth match of the season, their defence was not all it might have been.’ The correspondent went on to reflect, ‘Having said that, I must hasten to add that Celtic were far ahead in technique and thoroughly deserved to record their fourth victory of the season over the Fife club.’

ALL THE WORLD’S A STAGE…Sean Connery with Celtic legends Tommy Gemmell and Billy McNeill.

The Ibrox side’s occupation of the pinnacle was short-lived as Celtic played on the following Monday evening and they only required a reasonable degree of competency to overwhelm a feeble Falkirk team 5-0 at Parkhead. A lot of the talk before the game was centred on the European Cup semi-final draw which had paired Celtic with the champions of Czechoslovakia, Dukla Prague. Not a lot was known of the Czech Army team apart from the fact their most notable personality was cultured midfielder Josef Masopust, who had been named European Footballer of the Year in 1962. At the age of thirty-six, though, some observers, in football parlance, thought he was now ‘in bus pass territory’.

Jock Stein immediately delved into the Czechoslovakian fixture list to see if he could find a suitable date to watch Dukla; the Celtic manager detested going in ‘blind’ against opponents. It was obvious, however, Celtic had a major obstacle to overcome if they were to prove worthy of a place in the European Cup Final in Lisbon on May 25 where their opponents would be either the contrasting duo of Inter Milan or CSKA Sofia, who were drawn in the other semi-final. Big Jock was a man who explored and investigated rivals with a ferocious need to know.

He had already discussed the Dutch upstarts of Ajax with his good friend Bill Shankly, the manager of Liverpool. The Amsterdam team, largely unknown outwith their borders, had decimated the Anfield side 5-1 in the first leg of their second round European Cup-tie in Holland. They had galloped into an unassailable four-goal interval lead and the English champions’ only response was a last-kick-of-the-ball counter from Chris Lawler. Unusually dismissive of opponents, Shankly claimed the result was a ‘complete fluke’ and Liverpool would turn it around in the return on Merseyside. Ajax twice led before the game settled at 2-2 and the Dutch progressed on an overwhelming 7-3 aggregate. A young player by the name of Johan Cruyff had scored three goals over the tie. Stein, with his natural curiosity, quizzed his friend on the merits of the stylish Amsterdammers.

Shankly assured Stein Ajax had deserved their victory, he had no complaints and admitted he had witnessed something completely new in the construction of a team’s tactics. Of course, the system later became known as ‘Total Football’, but, in the sixties, this was a brand new concept and it was highly unusual to witness outfield players who were naturally comfortable in every position within the structure of the team. ‘John’ – as Shankly persistently called the Celtic manager – was told Ajax had the players and strategy to turn football on its head and win the European Cup that season. The Liverpool boss was not known for his wild speculation or outrageous predictions. Stein took everything he said on board and decided to travel to an Ajax game at some point in the near future. However, Dukla Prague, skilful and methodical, derailed Cruyff and Co at the next stage of the competition. The Czechs achieved a 1-1 draw at the old De Meer stadium, with a capacity of 19,000, and edged a tight affair 2-1 in Prague. Without watching them live, Stein realised they were a team of some pedigree and quality.

Before that appetising double-header against the Czechs, though, there was the urgent requirement of another two points against Falkirk that would catapult Celtic back into pole position in the defence of their First Division title. Jimmy Johnstone, suitably chastised, was back in his familiar position at outside-right with John Hughes still wide on the opposite flank. The Brockville side resisted the champions’ varied assaults until the twenty-fifth minute when Johnstone plonked a pass in front of Stevie Chalmers. His first shot was blocked, but he latched onto the rebound and fired home from close range. The canny, calculating Bertie Auld doubled the advantage before half-time with an ingenious lob from the edge of the box that sailed high into the net.

The goal of the game, though, belonged to Hughes, in the sixty-sixth minute, when he decided to go on one of his trademark solo runs with a net-bursting twenty-yarder to complete his impromptu act of defence-shredding ability. Falkirk’s lumbering centre-half Doug Ballie welcomed Johnstone back to the fold by flattening him a minute later and Tommy Gemmell flashed in the inevitable spot-kick. Chalmers collected the fifth shortly afterwards. After a solid night’s work, Celtic were top of the league by two points, with a total of forty-eight from twenty-seven games.

Almost unnoticed in the midst of the frantic football action, Joe McBride’s season had come to a halt. The centre-forward had been forced to admit he would not be in action until the new campaign got underway following a cartilage operation at Killearn Hospital in Stirlingshire. Jock Stein expressed sympathy for the player and at the same time had a sideswipe at the rumour-mongers who insisted McBride’s career was over. He said, ‘The specialists have advised Joe to give his knee complete rest over his period of recuperation. Of course, Celtic will miss him and what he gives this team, but we want him back to full strength and we accept the decision of the surgeons. However, Joe has proved over and over again he can deal with challenges and we look forward to him taking up where he left off in the new season. He has got a lot more goals to score for Celtic Football Club.’

PICK IT OUT…Tommy Gemmell blasts an unstoppable penalty-kick past Queen’s Park keeper Wilson in the 5-3 Scottish Cup success in March 1967.

The blow, of course, had been lightened by the arrival of Willie Wallace and that was highlighted on a wintry Saturday afternoon in Edinburgh on March 25 when the versatile international returned to face his former Hearts team-mates at Tynecastle. A crowd of 25,000 was in place by the time of the kick-off and there had been talk of Wallace being given a hostile reception from the home supporters after his supposed ‘defection’ to Celtic. If that talk was expected to mess with the player’s head it was a waste of someone’s time. Wallace simply responded with, ‘I’m a Celtic player now, we’re top of the league and that’s where we want to stay. I’ll do everything I can to guarantee a win. It doesn’t matter that it’s Hearts or anyone else, two points are our priority.’

Wallace was as good as his word as he notched a clever second goal direct from a free-kick in Celtic’s 3-0 victory in the freezing capital. Bertie Auld claimed the opener three minutes from the break when goalkeeper Jim Cruickshank could only beat away a Jimmy Johnstone cross to the edge of the penalty box. The midfielder, poised like a cobra, waited for the ball to drop before volleying a sweet left-foot drive into the exposed net. Just after the hour mark, Wallace’s bones were rattled by former team-mate Chris Shevlane, a hard-working right-back who would join up at Parkhead in the summer on a surprise free transfer.

Wallace placed the ball about twenty-five yards out and foxed his old friend Cruickshank with a deliberate low shot into the corner. The keeper didn’t even move. With five minutes remaining, Tommy Gemmell was given the opportunity to put the result beyond doubt when Celtic were awarded a penalty-kick. The left-back looked aghast when his effort was saved, but referee Archie Webster immediately ordered a retake, presumably for Cruickshank moving before the kick was taken. Gemmell accepted the opportunity to make amends and bulged the net on this occasion.

The games were coming thick and fast as the final tape to the campaign beckoned. Celtic now had to face Partick Thistle on Monday night and a remarkable crowd of 30,000, sensing something wonderful was in the air, packed into trim Firhill to catch the latest thrilling instalment. Bobby Murdoch had hirpled out of the game against Hearts with an ankle injury and hadn’t recovered in time for the game in Maryhill. Willie Wallace took over his right-sided midfield role and looked as though he had played there all his career. And he threw in a goal, too, in a 4-1 victory that was anything as comfortable as the scoreline suggested. Thistle made life extremely difficult for their visitors that evening in Glasgow’s west end.

Bertie Auld wasn’t risked, either, as Jock Stein paired Wallace with Charlie Gallagher in midfield, the first time the duo had performed alongside each other. It worked a treat. But Jimmy Johnstone was the Celtic player who picked up the gauntlet in the inexorable, exacting and, ultimately, exciting trek towards two points. The little outside-right turned in a mazy, mesmerising display to defy the conditions of the uneven, bumpy surface. He was up against a doughty, indomitable defender in George Muir, who, in Scottish football circles, was known euphemistically as a ‘stuffy, wee full-back’. In plainer terms, the Thistle player wouldn’t think twice about attempting to launch an opponent somewhere near Great Western Road. It was a ‘tactic’ that wasn’t designed to win any accolades from aficionados of football or international recognition, but it was effective; some outside-rights of the era were terrified to trespass into Thistle’s half such was the fear Muir struck into their heart. If that was the case with Celtic’s little maestro, his disguise was perfect. Johnstone tore Muir and Thistle to shreds and set up the opening three goals.

The first came straight off the Barrowfield training ground and would have had Stein purring with delight in the dug-out. Johnstone lined up to take a right-wing corner-kick and Billy McNeill, as usual, sauntered to the edge of enemy territory to add his aerial threat to proceedings. Tommy Gemmell lined up on the left-hand side of the penalty area waiting for knock-outs and rebounds that he would despatch back from whence they came on a regular basis. However, Jinky signalled to his best pal Bobby Lennox to take up a position outside the congested six-yard area. Lennox, unhindered, retreated about twelve yards and Johnstone picked him out with a perfect execution and the striker did it justice with a supreme volley that saw the ball tear past George Niven for the crucial breakthrough goal just four minutes from the interval. Fittingly, it justified its acclaim as Celtic’s one hundredth league goal of the season.

At half-time, Stein warned his troops to maintain their concentration. Thistle, he knew, were dangerous on the break and they possessed a sharp frontman in Johnny Flanagan, a tricky, will-o’-the-wisp striker who had been linked with Celtic in the past. Big Jock admired Flanagan, but didn’t rate him as highly as Lennox and he didn’t see that he could play both in the same forward line. As luck would have it, it was Flanagan who piled the pressure on the Parkhead side that evening with the equalising goal seven minutes after the turnaround. Once again, the former winger utilised his acceleration to race onto a through pass and, unexpectedly, hit a shot on the run before Ronnie Simpson could set himself. Flanagan’s searing twenty-five yard effort flashed past the perplexed Celtic keeper and crashed into the net via the upright.

Johnstone answered the SOS. He teased and tormented Muir as he came in from the right, jinking one way and going another. Muir was helplessly beaten and wing-half Tommy Gibb attempted to close down the void without success. Johnstone curled a cross impeccably onto Stevie Chalmers’ head and Niven was picking the ball out of the net for a second time in the fifty-ninth minute. Eight minutes later, Wallace, from another accurate right-wing corner-kick from Johnstone, hit a first-timer that skidded on the slippery surface and eluded the desperate dive of the veteran keeper. Chalmers made certain with another header following an excellent left-wing delivery from Gemmell.

The enterprising left-back never tired of extolling the virtues of his team-mate and close friend Johnstone. ‘God only knows how many times I’ve been asked to name my most dangerous opponent. It’s an answer in two parts – on the field in competition, George Best; in training, Jimmy Johnstone. I faced Bestie a few times at club and country level and he was a magnificent player; tricky, two-footed, good in the air and, forget those slender looks, as hard as nails. Jinky? What can I say? I looked at him during games and just thanked my lucky stars I was in the same team. I could see him right in the mood before some matches and I knew some poor left-back was going to get the runaround from the Wee Man. What was it Liverpool defender Emlyn Hughes said after a Scotland v England game? “I came off the pitch with twisted blood,” was his great quote. More than a few must have felt the exact same condition after Jinky went to work on them.

‘I faced Jinky every day in training, of course, and you hoped he wasn’t in one of those moods to continually thrust the ball through your legs and run around you shouting “Goodbye!” as he did so. Trust me, it wasn’t funny after awhile. I would say to him, “Do that again, you wee so-and-so, and I’ll kick you up the backside.” He never responded to threats. Unfortunately, If anything, it spurred him on to do it again and again. Every now and again Big Jock would look over and shout, “Right, Jinky, that’s enough of that. We’re here to train – get on with it.”

‘On those occasions, you were thankful the manager was in the vicinity to put an end to that morning’s torture. There was no badness in Jinky and he wasn’t attempting to show you up or anything like that. He just had this tremendous sense of mischief and fun although I have to admit there were times when I wondered about his particular sense of humour. Especially when I was on the receiving end.’

TOMORROW: CZECHMATE AND LISBON, HERE WE COME!