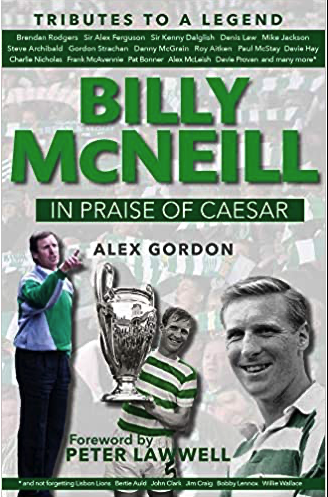

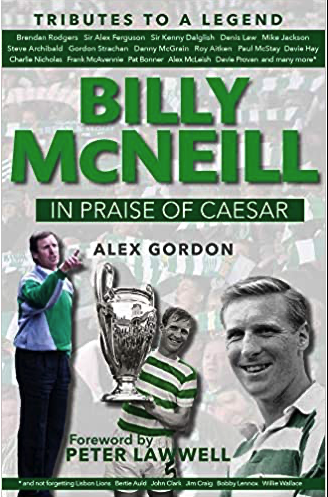

CQN continues its EXCLUSIVE series to salute Celtic’s Greatest-Ever skipper Billy McNeill.

Author Alex Gordon, who has had fifteen Celtic books published, including ‘Caesar and The Assassin‘ and ‘Lisbon Lions: The 40th Anniversary Celebration‘, interviewed many of the club legend’s team-mates and opponents for his tribute tome, ‘In Praise of Caesar‘, which was published in 2018.

Over the next week or so, CQN will publish a selection of edited memories. Today John Hughes has his say.

Please enjoy.

I WAS with Billy McNeill on the day he celebrated his twenty-fourth birthday.

I recall he was in considerable pain after sustaining a back injury six nights earlier following some robust buffeting from rugged Slovan Bratislava opponents during the first leg of the European Cup-Winners’ Cup quarter-final at Parkhead on a raw Wednesday evening on February 26 1964.

As expected, the confrontation against an unfussy Czechoslovakian team had given all the indications of settling into a fairly towsy affair mere moments after Belgian referee Valentin Triochal had blown to set the game in motion. The Czechs had no intention of putting on an extravagant show for the 55,000 fans in our ground.

We weren’t in the least surprised when Slovan retreated immediately behind the ball and formed a human barrier in front of their keeper. In the previous round, we had rampaged to a 3–0 home first leg triumph over Dinamo Zagreb, of Yugoslavia.

Early on, I thumped a header against the crossbar following a Jimmy Johnstone right-wing corner-kick. In the end, Bobby Murdoch settled a nervy occasion by tucking away a penalty-kick in the seventieth minute after the persistent Stevie Chalmers had been sent spinning by a wayward challenge from a panicking defender.

However, the victory came at a cost. Big Billy complained afterwards of some discomfort in the base of his spine. As usual, he had been bumped and barged as he had made his way upfield to take his place in the opponents’ penalty area when we forced a set-piece situation.

YOUNG YOGI…a teenage John Hughes in action for Celtic in the early sixties.

I got the same treatment. They looked at Billy and me, two guys over the six-foot mark, and decided we would get their undivided attention. They would try to block your run, they would get a hold of your jersey and you would feel something sharp digging into your ribs when you were airborne, it could have been an elbow or a knee.

We got similar attention in domestic games, but our European foes seemed to be a little bit more adept at these things.

Billy had been sufficiently injured to fail a fitness test before the league game against East Stirling at Parkhead three days later. John McNamee filled in at centre-half and we won 5–2 against opponents who were relegated from the 18-team First Division at the end of the season.

The race was on to get our inspirational captain fit to play in Czechoslovakia in four days’ time.

On March 3, the day before the return leg, his twenty-fourth birthday arrived and it wasn’t one of his most memorable. He had been ordered to refrain from any unnecessary physical activity. And Billy wouldn’t have been helped by the forty-mile coach trip from Vienna to reach the team’s destination the previous evening.

But he was passed fit to play in the tie that had an afternoon kick-off because Slovan’s spartan ground did not possess floodlights.

I recall the playing surface being unusually good considering it was March and we had been informed there had been some severe frost in most parts of Bratislava. The ground staff must have worked overtime to get the game played which made me believe they were eager to get on with the job at hand and prepare for a place in the semi-final which was due the following month.

I believe the game had gone something like ten minutes or so when John Clark took a sore one from an over-eager Czech. Wee Luggy never stayed down, he saw that as a sign of weakness. But he writhed on the ground after that ‘challenge’, for the want of a better word, and I could clearly see he was in pain as he got back to his feet, helped by Neilly Mochan, our trainer.

Remember, these were the days before substitutes. To me, Luggy was out of the game, but, as so often happened in these circumstances, he was stuck on the wing where he could be of nuisance value. Big Billy would have to play the remaining eighty or so minutes without his usual defensive colleague.

Bobby Murdoch was pulled back from inside-right to play in the position and we just took it from there. It was all a bit haphazard and slapdash, but, astoundingly, it worked.

With only five minutes remaining, I collected the ball around the halfway mark and it wasn’t in my mind to go for goal. I was probably a little surprised when Jim Kennedy shoved a short pass to me because the man known to everyone as ‘The Pres’ would normally put his foot through the ball and hoof it from one end of the pitch to another and we were invited to chase after it.

On this occasion, for whatever reason, he knocked it to my feet. There was a quick thought to take it down the line in an attempt to waste time, try to force a corner-kick or a throw-in and give my team-mates a chance to regroup and come forward.

I could have tried to hold onto the ball, too, and encourage my colleagues to join me in Slovan’s half, but I could sense there were a lot of tired limbs out there. I actually lost control of the ball, but quickly got it back and then I simply picked up momentum. I went past about three challenges when suddenly there was one last Slovan player between me and their goalkeeper.

I didn’t wait for him to make up his mind about coming out to meet me. While he was still trying to sort that one out, I slipped the ball past him and chased after it as he tackled fresh air.

Now it was me and Villiam Schroif. In these situations you do not even consider that the guy in front of you is a world-class goalkeeper. Simply put, he was just another bloke to beat if you wanted to score a goal. He came off his line as I took a moment to compose myself. I waited for him to commit, but he was too experienced to sell himself.

He remained on his feet, I saw a vulnerable space and hit a swift shot. The ball flew beyond him and thumped into the net.

It was the strangest experience. Apart from my team-mates and our backroom staff on the touchline, there wasn’t a cheer to be heard in the vast, old-fashioned stadium. There were around 30,000 Slovan fans in the ground that day and they had been struck dumb. My goal certainly wasn’t in the script. On this occasion, silence was, indeed, golden.

That goal was undoubtedly one of the best of my career and it took most of the headlines. That’s normal for goalscorers; it’s almost part of the job description. We get the applause and the sterling efforts of the guys at the back are often overlooked.

And that is my point exactly. I would never have been in that position to score that goal if it hadn’t been for the outstanding and unselfish work done that afternoon by Billy McNeill and the boys in defence. We could have been about three goals down before I scored. The Czechs bombarded us.

They decided to go route one with half-an-hour or so to go and were launching the ball in and around our penalty box. But Big Billy remained in control, stamping complete authority on the game. For me, it was easily one of his finest games for Celtic. The sad thing is that hardly anyone was there to witness it.

My old mate’s immaculate and commanding performance against Slovan has hardly rated a mention in the club’s folklore. You’ll have to take my word for it, Billy was unbeatable in the air and on the ground that day. And he didn’t complain once about being in pain.

That’s what made Billy McNeill that little bit special.