TODAY CQN brings you the twelfth EXCLUSIVE extract from Alex Gordon’s book, ‘CELTIC: The Awakening’, which was published by Mainstream in 2013.

The book covers the most amazing decade in the club’s history, the Sixties, an extraordinary period when the team were transformed from east end misfits to European masters.

THIRTEEN days after Lisbon, Celtic provided the opposition for the legendary Alfredo di Stefano at his glittering Testimonial Match at the Bernabeu Stadium. This was to be no friendly occasion.

Bertie Auld recalled, ‘Big Jock took me aside and told me, “Real Madrid are desperate to do us. We’ve just won the European Cup, but they still think they are best team in Europe. Amancio is their main player – do your utmost to keep him quiet. Keep an eye on him. I want to win this one.”

‘John Cushley was reserve centre-half to Billy McNeill at the time and he was one those rarities, a well-educated footballer! He could read and speak fluent Spanish and he told us what Real Madrid were saying about us in the national press. Basically, they were informing everyone that Celtic had merely borrowed the European Cup from Real for a year. Oh, yeah?

‘When we turned up at the Bernabeu the place was a 135,000 sell-out, everyone in Madrid appeared to want to see the great Alfredo for the last time in that famous all-white kit of Real. He was forty-years-old at the time, but still looked incredibly fit. He kicked off and lasted fifteen minutes before going off to the sort of hero’s accolade he undoubtedly deserved after such an incredible career. However, when he disappeared up the tunnel, the real stuff kicked in. Now we would see who was the best team in Europe.

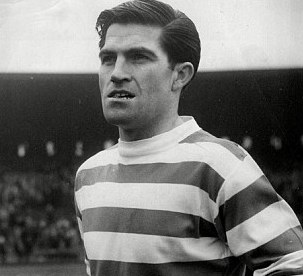

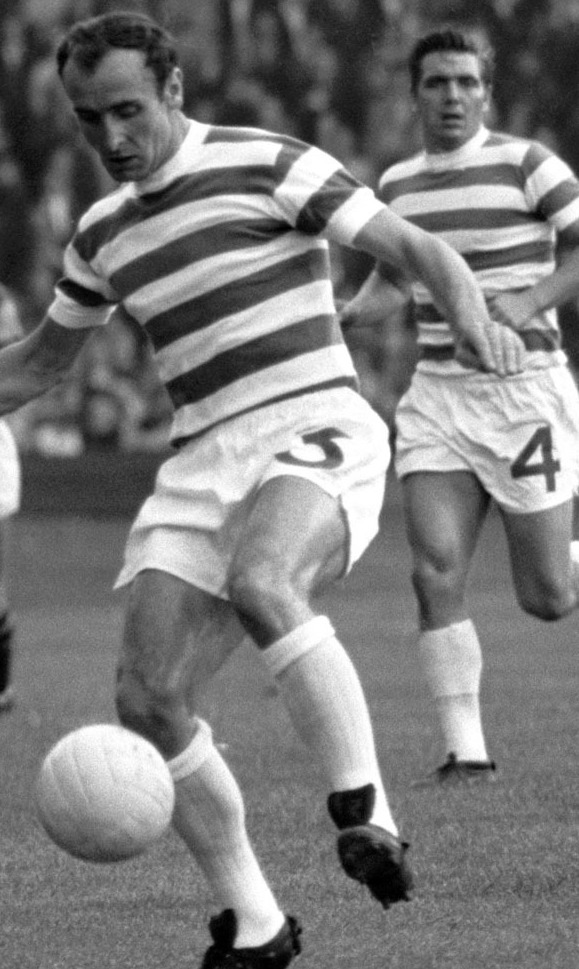

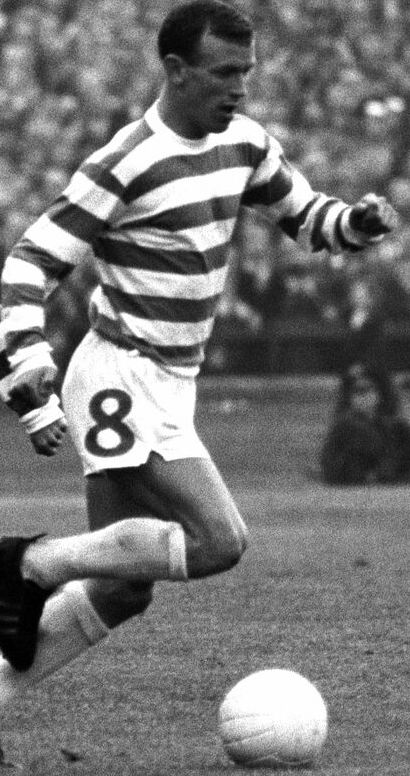

JIMMY JOHNSTONE…marvellous in Madrid.

‘Wee Jinky was unbelievable that night. He was simply unstoppable. It looked as though he wanted to put on a special show for Di Stefano who, along with England’s Stanley Matthews, was Jinky’s idol when he was growing up. The Real players were queuing up to kick our little winger, but he was simply too good for them. They just could not get the ball off him. Even I felt like applauding at times. Honestly, it was an awesome array of talent Wee Jinky provided that night. That wasn’t in the script.

‘This was supposed to be Alfredo’s Big Night and here was this wee bloke from Viewpark, in Uddingston, stealing the show. While he was going about his business, Amancio and I were getting ‘acquainted’ in the middle of the pitch. He didn’t like the attention I was paying him and we had a couple of wee kicks when no-one was looking. Nothing too serious, but enough for him to realise I was there to do a job for Celtic that night. Friendly? After Alfredo said his farewells, I don’t recall anyone, and I do mean anyone, pulling out of a tackle.

‘They were absolutely determined to hammer us and, equally, we were just as committed to the cause to show we were worthy European champions. Just borrowed the European Cup? It was just unfortunate for them we had a bloke who could read the lingo.

‘Amancio and I were still going at it when, suddenly, there was a 50/50 ball and we both went for it. Crunch! There was a bit of a fracas. He threw a punch and I felt the need to return the compliment. The referee was far from amused. If he thought he was turning up that night to simply swan around the place taking charge of a routine friendly, then he must have been in for a real shock. Here were two teams going at it hell for leather. But they would be doing so without any more input from me or my friend Amancio – we were both sent off. To be honest, it was a fair decision because we were both as bad as each other. As I walked past Big Jock in the dug-out, I looked over and said, “Problem solved, Boss.” He had the good grace to laugh.

‘It was Jinky’s night, though. He was at his elusive best. I recall one of their defenders, I think it was a so-called hardman called Grosso, coming out to the right to give the Wee Man a dull one. He clattered into him and down went Jinky. The Real player then turned his back and returned to the penalty area to take up his position to defend the resultant free-kick. He must have been alarmed when he looked round and saw Jinky back on his feet and preparing to take the award.

‘He was irresistible. Maybe he thought he had to make up for Lisbon where he stuck to the team plan. In Madrid, though, he had the freedom of the pitch. It was apt that we won 1-0 and Jinky – who else? – set up the winner. He took a pass from Tommy Gemmell on the left, skipped past a couple of tackles in that effortless style of his and slid the ball in front of his great mate Bobby Lennox. Bang! Ball in the net. Game over.

‘Even the Real Madrid players must have admitted we were true masters of European football after that exhibition. To be fair to their support, they started to applaud Celtic and, obviously, Jinky, in particular. He would sweep past one of their own players and the fans would shout, “Ole!” It was a night for our wee magician to display his tricks and flicks. He didn’t let Alfredo down.’

SEEING RED…Bertie Auld dismissed in Di Stefano’s Testimonial Match.

The serious European business kicked off again on 20 September and Jock Stein fielded the same line-up that had won in Lisbon in the opening defence of the trophy against the tough Soviets of Kiev Dynamo. Sadly, Celtic made some unwanted history on this occasion as they became the first holders of the trophy to go out of the tournament in the opening round. It was also Celtic’s first defeat in Glasgow in European competition.

The timing that was impeccable in Lisbon deserted them in Glasgow four months later. Unfortunately, too, the first leg would be at home. The psychological advantage was already with the Russians. There was an unusual slackness in Celtic’s early play as they faced Kiev that evening. The 55,000 fans, obviously still on a high and anticipating another wonderful European adventure on the club’s newly-found magic carpet, chanted, ‘Attack! Attack! Attack!’ for a full fifteen minutes before kick-off and continued raucously as the game made its early progression. By half-time, there was silence and concern with the Soviets two goals ahead through efforts from Valentin Pusach and Anatoly Byshovets.

Gemmell, hero of Lisbon, admitted, ‘I don’t think we got caught up in the atmosphere or anything like that. We were used to that sort of thing. Aye, we were aware the fans were shouting, “Attack” over and over again, but that was the way we always played, anyway. As I recall, I got down the wing in the first minute or so and fired a shot into the sidenetting. Another couple of inches to the right and who knows? Certainly, it had beaten their keeper. However, we left ourselves open at the back and they took full advantage.

‘Bobby Lennox pulled one back in the second-half and we piled forward, still taking risks at the back. It ended 2-1, but I can tell you we were convinced we would get back into it over there. We had already played Kiev in Tiblisi two years earlier, so it wasn’t like we were going into the unknown. I scored in that game as we got a 1-1 draw and went through 3-1 on aggregate. We knew we could win in Kiev if we got a break.’

Unfortunately, the bounce of the ball, quite literally, was against Celtic in the return. Bobby Murdoch, so influential and so important in the engine room of the team, was dismissed by Italian referee Antonio Sbardella for throwing the ball to the ground after yet another strange decision from the match official. Murdoch had already been booked in the first-half for dissent and Sbardella looked as though he couldn’t wait to punish him further just before the hour mark as he hastily pointed to the dressing room.

EARLY EXIT…Tommy Gemmell and Co had no luck against Kiev Dynamo.

Bobby was crestfallen,’ recalled Gemmell. ‘He burst into tears and was inconsolable for hours afterwards. We reminded him that it was an Italian who had been put in charge and maybe he was an Inter Milan fan. He certainly acted like it in Kiev. Billy McNeill had the ball in the net and it looked okay to everyone, but it was ruled out. Big John Hughes came in for Stevie Chalmers that night and he netted after one of those mazy dribbles of his, but the ref called it back and awarded Kiev a free-kick for some unseen infringement. A Steward’s Enquiry might have come in handy around this time. One thing was certain – most of the 85,000 fans in the ground that night weren’t complaining about the ref’s performance.’

Remarkably, Celtic went ahead only two minutes after Murdoch’s ordering-off when Lennox levelled the tie on aggregate, snapping a free-kick delivery from Auld beyond a startled Ivan Zanokov. But Celtic still needed another because the goals away counting double rule had been introduced by UEFA at the beginning of that season. So, 2-2 would still have seen Jock Stein’s men topple out of Europe.

The fates were conspiring against them. With one minute remaining, Celtic, who had dominated even with a man short for half-an-hour, earned a corner-kick. Gemmell said, ‘There was nothing else for it but for everyone to pile into their box. At that stage we knew we were out, so we had nothing to lose. They left one player, Byshovets, on the centre spot as they came back to defend the award. He was on his own, every Celtic player, barring Ronnie Simpson, of course, was in the Kiev penalty box. The ball came over, was hacked clear and, unfortunately, went straight to Byshovets. Honestly, it could have gone anywhere.

But a wild boot out of the box turned into an inch-perfect pass. We all chased wildly back, but it was a lost cause. He tucked the ball behind Ronnie and that was that. I’m not being churlish or unsporting, but, in truth, we had played Kiev off the park for three of the four halves over the two games. Make that three-and-half. They didn’t contribute much more than the twenty-five minutes in the first leg that were to prove so crucial. Yet we were out and they were through. We paid a very heavy price for a wee bit of hesitancy early in the game at Parkhead.

‘I remember Big Jock was very positive after the match. He realised he couldn’t have asked for anything more from his players in Kiev. The referee was dodgy, no doubt about it. Whether something untoward was going on or he was just rank rotten, we will never know, but he gave everything to our opponents that night. Jock knew it. We knew it. So, we travelled home, at least, with the consolation we had not been hammered out of sight by far superior opponents. Big Jock also understood he would have to get our heads up for our games against Racing Club of Buenos Aires with the first leg due at Hampden in a fortnight’s time. He said, “If we can’t be European Cup winners again, let’s be the best team in the world.” That uplifted all our spirits. It was an appealing thought.’

Unfortunately, ‘appealing’ was not the word anyone around Celtic was using after three brutal confrontations against an odious bunch of thugs masquerading as footballers in the officially-named Inter-Continental Championship trophy. It was the so-called reward for the European champions to meet their South American counterparts to decide who would be acclaimed as the World Club winners.

‘It was the night fitba’ went oot the windae,’ was the way Jimmy Johnstone remembered the shocking first leg against the unscrupulous Argentines. He didn’t need to be too eloquent, but those nine little words summed up with sublime perfection that night in Glasgow on 18 October.

‘The Wee Man nailed it,’ said Bertie Auld. ‘No-one could have put it better. Listen, I can take someone kicking me. When you can play in the Scottish Junior football as a teenager, there is nothing left to frighten you on a football pitch. As a kid, I was told my leg would be broken in so many places by so many hulking brutes in my short time at Maryhill Harp. Sometimes it was my jaw or my neck or my arm or my back or my nose. It didn’t bother me one bit. As long as they could take it back!

ARGY BARGY…Billy McNeill and his Celtic mates faced a whole new ball game against Racing Club.

‘But I defy anyone to accept someone spitting in your face. Where I came from in Maryhill you sorted out your problems with your fists. No-one would ever have even thought of spitting. That would have been seen as cowardly and, yet, it seemed completely acceptable to the guys who wore Racing Club’s colours in our three games against them. I still find it difficult to call them players. They would wait until the ball was fifty yards or so away with the referee and his linesmen following play and they would sidle up and gob in your face. Then they would run away leaving you to wipe their spittle off your face. If they did that to you in the street you would be after them to sort them out. But they hid on the football pitch where they were protected by a gullible referee.

‘They were sleekit, yes, that’s the word, to disguise what they were doing. The fans would miss the initial reaction and then spot your retaliation. Look, I loved my football, still do, and I thoroughly enjoyed most of it as a player and as a manager, but I never dwell on those encounters. The entire episode from start to finish was just a nightmare. Unfortunately, we couldn’t handle it and eventually cracked in the play-off in Uruguay. We were only human, after all, and there is just so much we could tolerate, so many times you can turn the other cheek for some cretin to spit on it.

‘Manchester United, following their European Cup triumph the year after us, got the same treatment in their games against Estudiantes. I had warned my pal Paddy Crerand to watch them carefully. He might have thought I had been exaggerating until he telephoned one night after their two meetings with that particular rancid gang of Argentines and said, “My God, Bertie, you weren’t kidding, were you?” Later on Ajax, Bayern Munich and Nottingham Forest declined to participate against their South American opponents. What was the point of seeing the likes of Johan Cruyff, Franz Beckenbauer and Trevor Francis putting their careers on the line to win any title?

‘Who was running the show, anyway? FIFA, the world’s governing football body, presided over the tournament, but UEFA, the European wing of the organisation, didn’t seem to be too involved. I found that strange. We were representing Europe, after all. Certainly, they didn’t even have match observers at our three games against Racing in Scotland, Argentina or Uruguay. You can be certain, though, that they would have helped themselves to a hefty percentage of the gate money from the Hampden game. Maybe if they had sent a representative along to the first match they might have deemed it wise to lobby FIFA about considering scrapping these crazy confrontations.

‘Someone took the decision to make the occasion a one-off final at a neutral venue in 1980 and that format remained in place for decades. If that had been the case in 1967, I have no doubt Celtic would have been acclaimed as world champions. No-one, by fair means, could have beaten us. We came back from South America knowing we were the best team in the world. Sadly, we didn’t have a trophy to show for it.’

What should have been a showpiece spectacle for global football to embrace was, in truth, a shambles. Once again, Celtic had to play the first match in Glasgow and that didn’t work in their favour, either. If the games ended in a tie, the play-off would be held in South America. Neither goal difference nor goal average would come into it. It was on a points system based on league formats; two points for a win, one for a draw, zero for a loss.

Racing Club were offered the choice of three referees – an invitation that was also extended to Celtic in Argentina – and, as a Spanish-speaking nation, they, unhesitatingly, went for an official called Juan Gardeazabal, who happened to be a Spaniard. Sadly, for Celtic, he didn’t speak a word of English. Auld recalled, ‘During the game in Glasgow we could hear him conversing with their players, but all we got were shrugs and gestures when we tried to query anything. It didn’t help much, either, that he frowned on heavy tackles that were perfectly legal and something we did every matchday in Scotland. He understood the Latin-style of play and that certainly favoured Racing Club when, on that rarest of occasion, they were quite happy to kick the ball and not an opponent.’

A crowd of 83,437 turned up at Hampden Park to witness what had been billed the biggest club game ever staged in Scotland. Prime Minister Harold Wilson was in the VIP seats. Stein rarely tinkered with his defence and was satisfied to go with the Lisbon Five: Simpson; Craig, McNeill, Clark and Gemmell. Murdoch and Auld again got the nod to patrol the midfield and do most of the link-up play. The trickery of Johnstone and the pace of Lennox, he knew, would give the Racing Club defence problems if they were allowed to play. That turned out to be a big ‘if’.

THE LONG WALK…John Hughes sent off against the Argentines.

Wallace, who could look after himself, was in, too, so it was now a straight choice between European Cup matchwinner Stevie Chalmers or John Hughes with the latter getting the go-ahead. Stein liked to keep pre-match routines as normal as possible. After going through the tactical work that had been detailed the previous evening at the hotel on the Ayrshire coast, he appeared to be spending an inordinate amount of time as the clock ticked down to the kick-off going over ground he had already covered.

As John Clark said, ‘He rarely repeated himself.’ Now, though, he was telling the players for the umpteenth time, ‘Don’t let them put you off your natural game.’Or ‘Don’t get drawn into any feuds.’ Or ‘Don’t retaliate. That’s what they will want you to do.’ Or ‘If you lose your discipline, you’ll lose the game.’ Or ‘Let the world see how to win the Celtic way.’ Auld recalled, ‘There was a genuine concern from The Boss. He must have been exhausted just going through his team talk. Big Jock was meticulous, as everyone knew, but he just seemed a wee bit more cautious than normal on this occasion.’

Within minutes, the Celtic players realised why their manager was fairly apprehensive about the conduct awaiting them out on that football pitch. Jimmy Johnstone was the target. With just about his first touch of the ball he was sent spinning into the air after a crude lunge from Juan Rulli. With the outside-right still coming back to earth, he was met with another so-called challenge from Oscar Martin. Johnstone went down in a heap. Auld remarked, ‘I thought they were trying to volley the Wee Man over the stand and out of the ground. I looked at the referee and wondered what action he would take. He didn’t even admonish either of the villains. My heart sank.’

The Racing Club players immediately realised Senor Gardeazabal was a weak referee. He had opened the door for Scotland’s national stadium to become a clogger’s dream, a hacker’s paradise. The Argentines took full advantage. They set about abusing their opponents from that moment on with Johnstone feeling the full brunt of their punishment. It seemed their priority was to put the Celtic player in hospital that evening.

Jim Craig observed, ‘People often talked about the undoubted skills of the Wee Man. One thing quite often overlooked was his courage. He would be scythed down, bumped, thumped, kicked, punched, elbowed, knocked about like a rag doll, but he always came back for more. Jinky gave you the impression an Elephant Gun might be required to stop him and keep him down, but I doubt if that would have worked, either. He was unbelievably brave.’

Opportunities were at a minimum against a defence that was happy enough to give away fouls anywhere within a thirty-five yard radius of their goal. They got a fright, though, ten minutes after the turnaround when Auld slung over a beautifully-judged deadball effort and Billy McNeill’s header bashed against woodwork. The Celtic skipper had better luck when Hughes swung over a right-wing corner-kick later on. McNeill had been blocked and jostled any time he had come forward for corners or free-kicks.

‘That happened in every game and I was used to it,’ said McNeill. ‘They were a bit more sly or cunning than anything I had encountered in our game at home, but I always kept my concentration. Their aim was to distract you and I wasn’t going to let that happen.’ Hughes flighted over ball just off centre of the goal about twelve yards out. Unbelievably, McNeill found himself with a yard or so of freedom. He leapt, made solid contact and watched in expectation as the ball almost lazily arced away from stranded keeper Augustin Cejas and high past Jinky’s pal Martin into the net.

‘We all ran to congratulate Caesar,’ said Auld. ‘He broke off his own celebrations to have a quick word with Alfio Basile, who would later manage the Argentinian international side. Basile had tried to rough up our skipper time after time and it is to Caesar’s credit he refused to take the bait. Later I asked my pal, who could actually speak a little bit of Spanish, what he had said to the Racing Club defender. He was the picture of innocence when he replied, “You know, Bertie, I can’t quite remember.” I assumed he wasn’t asking him out for a drink afterwards!’

McNeill, however, did recall Basile’s reactions at the end of the game. ‘You get guys making all sorts of daft gestures as you head for the tunnel,’ he said. ‘Most of the Racing Club’s players were at it. Silly threats that are supposed to be menacing, but it is best to smile at these guys. They hate that. Show fear and you are a dead man in the next match. I remember Basile motioning with an imaginary knife that he was going to cut my throat. And, do you know, if he had carried out that threat on the pitch at Hampden that night there is every chance the referee wouldn’t even have booked him.’

There was a moment of honesty from left-back Juan Diaz afterwards when he was being interviewed by a South American journalist. He was quizzed about what he thought about playing against Johnstone. He answered in a rush of Spanish. Afterwards, the press man was asked for a translation by his Scottish counterparts. Diaz had said, ‘I tried to tackle him fairly at the start, but I realised this would be impossible for the entire game. I elected to kick him when he came near me after that. He would have destroyed me.’

Astonishing, then, at no time during the game did match official Gardeazabal elect to have a word with Diaz. Even more revealing, in a game riddled with fouls, is the fact that not one single player was booked. Maybe the good senor had left his little black book in Spain. Johnstone, sturdy individual of body and mind though he may have been, was in no fit state to play in the next game, a 4-2 league win over Motherwell.

The great South American adventure continued with the trip to Buenos Aires that lasted twenty-one hours with stops in Paris, Madrid and Rio. There was the usual obstructions that Celtic were now becoming to expect. The hotel was a wreck, the training facilities were a disgrace and the locals were hostile. Just a year beforehand, England manager Alf Ramsey had branded Argentina’s players ‘animals’ after their 1-0 World Cup quarter-final win over them at Wembley. Geography, along with football etiquette, was clearly not a strength in this part of the universe. England and Scotland appeared to be one and the same country according to most of the Buenos Aires population and it was a bit too late to argue the case.

Eventually, Celtic moved their HQ to the Hindu Club about thirty miles or so from the city centre. They were greeted with the sight of four policemen carrying machine guns. There were another twenty armed cops with shoulder holsters dotted around the complex and there was a twenty-four hour watch on the grounds. Auld said, ‘Did someone tell them we were there to start a revolution instead of play a game of football? It was all very surreal.’

Auld was forced to miss the game after injuring an ankle in the 5-3 League Cup Final victory over Dundee the day before the team flew out. He said, ‘I was desperate to play, but I knew Big Jock wouldn’t select me unless I was 100 per cent fit. I accepted that wouldn’t have been fair to my team-mates. As we were driven in our coach through Avellaneda, I have to say I was depressed at some of the sights we passed on the way.

‘Buenos Aires looked affluent enough, but we witnessed an awful lot of poverty and deprivation on the hour-long trip to the ground. Crumbling wooden shacks that were homes to some poor unfortunates, children wandering around on their own and dogs foraging for morsals of food on the streets. Now we understood why their players would run over children’s bodies to get their promised bonus of £1,500-per-man to lift the trophy. That would have been a fortune in that part of Argentina.’

Mr VERSATILE…Celtic’s unsung hero Willie O’Neill.

Celtic’s coach had to avoid several hundred Racing Club fans with obvious death wishes as they tried to postpone the journey by putting their bodies in front of the vehicle and pushing, shoving and rocking it from side to side at every set of red lights. The driver, obviously a local who had seen all this before, ignored the obstacles and steered a steady path. If someone wanted to headbutt his bus that was their problem. Eventually, the coach reached its destination, the monstrous oval-shaped, grey-walled Avellaneda Stadium.

Outside, cops, with massive sabres, on horseback pushed back supporters. There were other policemen with leather lashes who weren’t slow to use them if they thought the fans were getting a bit too excited. Cops with guns patrolled outside of the ground. Gemmell, like everyone else in the Celtic party, wasn’t too impressed. ‘It wasn’t even close to kick-off and they were already baying for blood,’ he said. ‘A few stared through the windows of our coach and made all sorts of weird gestures. They were all pulling hideous faces with gargoyle-like expressions. I began to wonder if we were still on earth. I don’t suppose they mentioned any of this in their travel brochures!’

Willie O’Neill, a left-back or midfield enforcer, got his pal Auld’s position in the team and Chalmers, his speed a vital factor, came in for Hughes from the team that had won at Hampden. Auld took his place in the stand alongside Hughes and Joe McBride. As they settled in, the three thought they felt a slight drizzle of rain. Warm rain. Auld looked up to the tier that ran directly above the Celtic party. ‘There was a group of disgusting lowlifes urinating on us. When one was finished, another would take his place. We were stuck right underneath them and couldn’t move in a packed stadium. Spat on in Glasgow and peed on in Avellaneda. I was beginning to agree more and more with Alf Ramsey.’

Celtic had also been warned the Uruguayan referee Esteban Marino was ‘not strong’. But just moments after the match official had led the teams out of the tunnel, the occasion was veering to what could have turned into a full-blown riot. Marino might not have a game to control, after all. Ronnie Simpson was felled by an object thrown at him as he went out to check his nets before the kick-off. There were massive wire fences behind both goals and it looked virtually impossible for an individual to throw something over it and down with any degree of accuracy. A more sinister thought was that the keeper had been assaulted by someone posing as a photographer or a character with an official pass hovering around the touchline behind the goal.

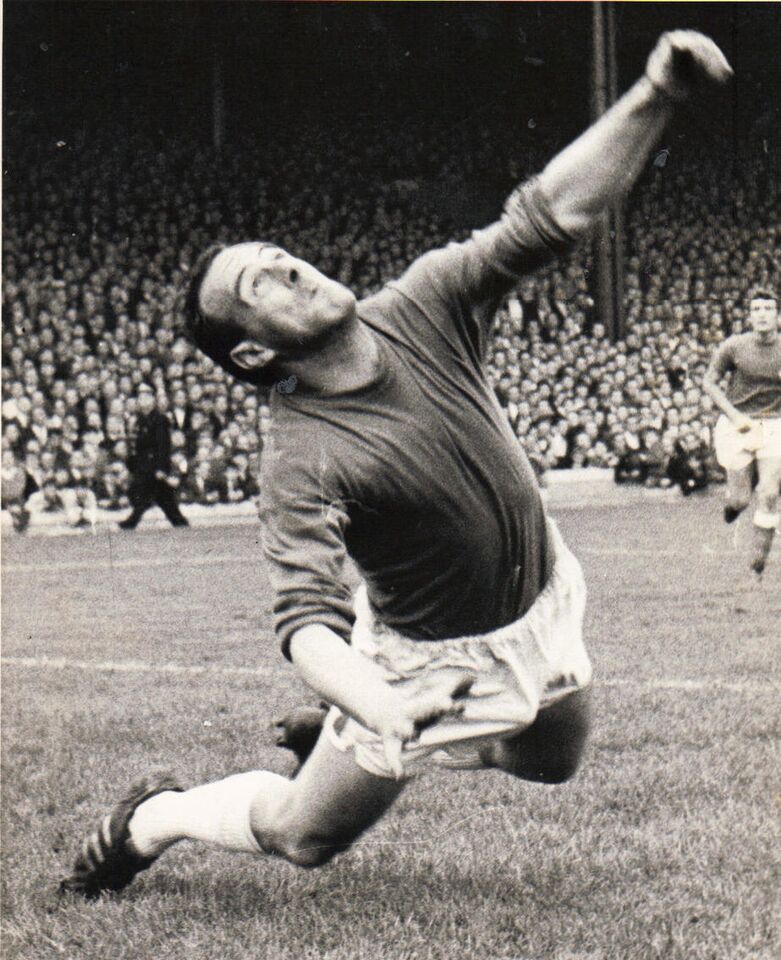

SHOCKER…Ronnie Simpson had to be replaced after being hit on the head by a missile.

After treatment, it was reckoned that Simpson had been hit by something heavy like a metal bar. Yet, a search of the immediate area only moments after he went down, failed to discover anything of the nature that could have caused such damage. Nothing nearby such as a brick or a bottle could be found. Clearly, whatever it was had been removed. By whom? No-one ever did find the mystery object. The trackside security later admitted they had failed to search the photographers’ camera cases. You could have got a bazooka in some of those enormous holdalls back then.

Robert Kelly hadn’t welcomed the thought of fulfilling the return leg obligation after the unacceptable behaviour of the Racing Club players in Glasgow. As you might expect, Auld was rightly concerned, as were the other players stranded alongside him in the stand, rows and aisles away from the Celtic officials. ‘If our chairman had called the players off the pitch at that point, then God only knows what would have happened next.

‘I don’t scare that easily, but I looked around me and all I could see were these ugly faces screaming and screeching abuse. We might just have made it to the sanctuary of the dressing room, but I genuinely doubt if we would have got out of that ground unscathed. I have been in the thick of all the emotions that run high in an Old Firm game, but the Glasgow derbies were tea parties compared with this. Everywhere you looked people were gesticulating and threatening, snarling and spitting. Welcome to hell.’

After a hasty confab between Kelly and the Celtic directors, they agreed, albeit reluctantly, to allow the game to go ahead, fifteen minutes late. In those most extreme of circumstances, there seemed little alternative. John Fallon took over from Simpson in goal. Astoundingly, in the midst of all the madness, Celtic were awarded a penalty-kick in the twentieth minute.

Auld said, ‘As you might expect, it was an absolute stonewaller. Jinky wriggled through and was sent clattering to the ground by their keeper Cejas. It was a clear goalscoring opportunity and, these days, would have brought an automatic red card for the keeper. Now that would have been interesting. I still shudder to think how the fans would have reacted to that.’

Gemmell placed the ball on the spot. ‘The Racing Club players were, as usual, doing everything they could to distract me. You would never have detected it at the game or on the television, but they were throwing little pieces of dirt or flicking stones at me and the ball. On the run-up, a clump of something or other went scudding across my path. I ignored it. I recall one game where I was about to take a penalty-kick and a shinguard was thrown at the ball. Didn’t bother me. I scored then and I scored against Racing. I enjoyed giving the ball an almighty whack at the best of times and here I was only twelve yards from goal with just the keeper to beat. I reckoned if I hit the ball as hard as I possibly could and got it on target then there was a good chance I would score.

‘There was little point in a keeper trying to second-guess me when I didn’t know which way it was going, either. Seemed a reasonable formula. I took a lot of pens, but I think I only missed two or three and I believe I hit the keepers with those efforts! I was always confident I would score, so the antics of the Racing players didn’t put me off one jot. I hammered it and the effort thundered past Cejas, who had advanced to about the six-yard line by the time I struck the ball. If he had saved it, I wonder if the referee would have been strong enough to order a retake? Doubt it.’

Alas, the lead lasted a mere thirteen minutes when Humberto Maschio, a tricky midfield customer, picked out Norberto Raffo, all on his own in the Celtic penalty area, and he looped a header over the stranded Fallon. Sweeper John Clark, who made such an exemplary job of controlling the back four, is convinced the goal shouldn’t have stood. ‘He was yards offside when the ball was played to him. Not just a shade off, but yards.’

BAFFLED…John Clark couldn’t believe the ref allowed Racing’s first goal to stand.

McNeill added, ‘Blatantly offside. No argument.’ Auld said, ‘From where I was sitting, I couldn’t see how he could be onside. I agree with John, he was in oceans of space and our back lot never afforded anyone that luxury. If you see photographs of that goal, you will notice that Raffo is completely on his own. However, after the referee had awarded us a penalty-kick, he was hardly like to rule out a goal by that lot, was he?’

The winning goal of the evening arrived shortly after the turnaround when Juan Carlos Cardenas, one of the rarities in this Racing line-up who seemed to genuinely want to play football, thumped one past the diving Fallon. The keeper had no chance. Racing, in front of their own howling banshee of a support, then retreated back into defence. For the next forty minutes or so they were rarely tempted across the halfway line.

Chairman Robert Kelly, in fact, didn’t want Celtic to play in the third game. However, Billy McNeill said, ‘Yes, we were all sick at the way we had been treated, but, deep down, we knew Big Jock was eager to show everyone we were the best club side in the world. He also believed the players might get better treatment in a neutral country. I think that’s what persuaded the board to go ahead with the game.’

Celtic requested the same referee, Esteban Marino, for the third game. It made a bit of sense, considering he was a Uruguayan and he would be officiating in his homeland. FIFA disagreed and awarded the game to Rodolfo Cordesal, a Paraguayan who was still to blow out the candles on the cake for his thirtieth birthday. Who was it who said common sense isn’t that common? The world’s footballing body seemed hell bent in wrecking their own blue riband climax to the planet’s biggest club competition.

Thankfully, Fallon had come through the Buenos Aires experience without any mishap and Auld had recovered from his injury to return in place of O’Neill. Chalmers also made way with Wallace moving into the main striking role and Hughes taking over at outside-left. When rookie referee Cordesal, who had just turned twenty-nine, put the whistle to his lips to signal kick-off at the Stadio Centenario in Montevideo no-one, not even Nostradamus, could have predicted what would happen next.

GROUNDED…John Fallon in action.

The first twenty minutes passed without any calamity or consternation although left-back Nelson Chabay, who had replaced Diaz, appeared to want to get inside Johnstone’s shirt at times. Diaz the honest man making way for Chabay the hatchet man. Seemed about the norm for Racing’s way of thinking.

Unfortunately, Cordesal didn’t twig that the Argentines seemed to have drawn up a rota to kick Johnstone. Chabay would hack him. Next time it would be someone else, who would be replaced by another until it came round to Chabay’s turn again. The crowd of around 60,000 weren’t quite as animated or intimidating as they were at the Avellaneda and that might have been down to the fact that 2,000 plain-clothed riot police mingled among them. The Uruguayan authorities were resolute in their policing of the game.

There would be no trouble on the terracings; pity they couldn’t do anything about the events on field. The match official awarded twenty-four fouls against Celtic in the first-half. Auld observed, ‘That was about as many as we gave away in an entire season at home!’

The fuse that had been lit in Glasgow burned all the way to Montevideo and was about to ignite another explosion of fireworks. Up it went just eight minutes before the completion of the first-half. Astonishingly, the first Celtic player to be sent off was Lennox, the same Lennox who could go through season after season without so much as a word in the ear from a referee. There was yet another melee and, once the torsos of both sets of players had been disentangled, Basile, the guy who threatened to cut McNeill’s throat, was being ordered off. As ever, he protested his innocence as he rubbed his jaw, as though he had been punched.

What happened next just up about entirely summed up the sorriest chapter in Celtic’s history. The match official had a word with the Racing player, Basile pointed to Lennox and the ref went over and signalled for the protesting Celt to leave the field. He had been banished, too. Lennox looked mystified. ‘Me? What have I done?’ he asked. Either Cordesal didn’t speak English or was hard of hearing, but he simply dismissed the protestations and walked away. Lennox made his way to the touchline, but was waved back on by Jock Stein. There had to be some mistake. Lennox about-turned and noticed that Basile was also still engaged in ‘discussions’ with the ref. He pointed at an injured colleague who was lying on the ground. Apparently, he wanted the crocked player to take the blame and go off in his place.

Lennox walked back on, Cordesal sent him off again. The Celtic player, still wearing a puzzled expression, trudged to the touchline where he was met by Stein once again. The Celtic manager, stopped his player, turned him around and propelled him back onto the pitch. The referee signalled to the sidelines and two soldiers with swords came on.

MARCHING ORDERS…Bobby Lennox was ordered off in Montevideo.

Lennox said, ‘The soldier was only a couple of feet away from me. He told me to get off. I looked at his sword. I headed back to the touchline. I could risk the wrath of our manager, I wasn’t going to argue with a soldier with a sabre. I headed straight for the dressing room.’ The argumentative Basile also thought the better of continuing his debate with the match official and beat a hasty retreat when another soldier, armed with a sword, headed in his direction.

Gemmell observed, ‘I was standing there with my arms folded wondering what the hell was going on. Bobby Lennox sent off? There had to be some mistake. He may have been a bandido on the golf course, but he wouldn’t say boo to a goose on the football pitch. Around this time, I could see that my colleagues, as well as myself, had had just about enough of this nonsense. We had now had to endure two-and-a-half games – fifteen minutes short of four hours – of the Racing players spitting on us, kicking us, pulling our hair, nipping us, och, basically going through the whole repertoire of dirty tricks.

‘They had picked on the wrong bunch of guys. I looked at Bertie, Bobby, Billy and the rest of the lads. John Clark was a cool customer, but he looked about ready to erupt. We weren’t going to accept any more abuse in the second-half. We knew we would not get any protection from a decidedly ropey referee. He had lost the plot, probably lost it around the time of the kick-off.

‘We were all getting frustrated at the ridiculous treatment of Jinky. The Wee Man could look after himself, but you do feel a bit helpless when you see your colleague being used as a football by a bunch of louts. Soldiers with drawn swords escorting one of our players off the field was not in the script, either. It wasn’t what we signed up for when we won the European Cup and then genuinely looked forward to playing against Racing Club. How naive can you get? We thought they might be honourable sportsmen. What a laugh. What a preposterous notion. Mind you, we realised that about two minutes into the game at Hampden when two of their defenders tried to play keepy-uppy with Jinky.’

Shortly after the interval, Johnstone, much sinned-against throughout, was dismissed, again in remarkable circumstances. Martin tried to remove his shirt once more and the player tried to wrestle free. His elbow appeared to hit the defender on the chest, but Martin went down clutching his face. That was enough for the ref to race over and point once again to the dressing room.

Auld said, ‘I caught the Racing players looking at each other. They were delighted. They were terrified of Jinky and the referee had come to their aid; they wouldn’t have to face him again. To a man, we knew we would not get justice that day. On a personal note, I was getting sick and fed up of players spitting on me. I wiped my hair at one stage and it was covered in spittle. You have to be an extraordinary individual blessed with the patience of a saint if you can accept that sort of behaviour from anyone.’

The mood didn’t get any better when Cardenas, who had scored the goal to take the game to Montevideo, rifled in a long-range effort for what turned out to be the winner in the fifty-sixth minute. Jock Stein later blamed stand-in keeper Fallon for not saving the thirty-five yard drive, but Auld jumped to his colleague’s defence. ‘I don’t think he had much of a chance. The ball swerved and dipped before it flew past him. Believe me, like our manager, I was a serial critic of goalkeepers, but I don’t think Fallon was culpable on that occasion.’

The game descended into anarchy with Racing now determined to do anything they had to do to hold onto their lead. The referee, who would probably never recover from this experience, couldn’t control the Racing players as they continually put the boot in. John Hughes was next to see red. He followed a passback to Cejas, in the days when the keeper could pick up the ball. The Argentine could simply have lifted it, but, to waste time, he collapsed on the ball.

As he lay there, Hughes tried to kick the object out of his hands. A definite foul, it must be admitted. What happened next, though, should have earned Cejas, who had been fairly theatrical throughout, a stick-on Oscar for Best Actor. He rolled around as though the Grim Reaper himself was in attendance. Off went Hughes and back to his feet got Cejas. A career in Hollywood beckoned.

Years later, Auld could laugh. ‘I asked Big Yogi what on earth was he thinking about.’ He replied, “I didn’t think anyone was looking.” Just the rest of the world!’ Hughes admitted, ‘Aye, I did say that and it has to come back to bite me for years. It seemed a reasonable thing to do at the time.’

Unfortunately, the TV cameras did catch another incident when play had stalled yet again. There was the usual posse of players from both teams arguing the toss over something when Gemmell came into the director’s shot to the left of the screen. Raffo, adept at the sneaky foul, was standing a few yards from the latest melee. The Celtic left-back raced forward at full speed and booted the Argentine up the backside. ‘That was inexcusable, I accept that,’ said Gemmell. ‘At the time I wasn’t thinking straight. Who would in the midst of all we had gone through? I can tell you that one of their players, I think it was their No.11, went along our back four of Jim Craig, Billy McNeill, John Clark and myself and spat in our faces immediately after the start of the game.

‘We had played these hooligans three times inside two weeks and everyone has a breaking point. Mine came in that moment. I looked at Raffo and he was obviously fairly pleased with himself. He was very clever. He jumped out of every tackle and we couldn’t catch him. He had got away with murder and not one of the three referees had even spoken to him. I decided to mete out a little bit of justice myself. Yes, I gave him a dunt up the rear end. It could have been worse – he could have come off that pitch with three Adam’s Apples!

‘It was only when I got home that I realised the entire incident had been caught on the telly. It’s a pity the TV editors weren’t quite as diligent in capturing the antics of our opponents, but they were a wee bit better in disguising their kicking of us. The game, in fact, was edited by the BBC in their London studios and they seemed to dwell on everything the Celtic players did and ignored what Racing were getting up to. It looked like extremely biased editing – maybe that old Scotland v. England thing – and I can tell you Big Jock was livid when he saw the edited tape. I don’t think he spoke to the BBC for about a year which was a bit harsh when you consider the lads in Scotland had no control over the final film.’

It was long overdue, but even Rulli couldn’t escape for three full games and, with five minutes to go and after another foul, he, too, was required to leave proceedings. A couple of minutes later, Auld clattered into one of the many culprits who had been dishing it out and down went the Racing player. The referee signalled for the Celtic midfielder to join team-mates Lennox, Johnstone and Hughes in the dressing room.

Auld said, ‘I shrugged my shoulders and basically told him I didn’t speak Spanish, so I hadn’t a clue what he was indicating. I looked him straight in the eye and realised he was in a state of panic, if not shock. He looked genuinely startled. I wasn’t arguing with him. I just wasn’t going off. I simply refused to move. What happened next surprised even me – he restarted the game with a free-kick to Celtic!’

MISTAKEN IDENTITY…Bobby Murdoch “sent off” against Racing.

Bobby Murdoch was surprised to later discover he had been sent off in the game, according to the referee’s official report. ‘Aye, that’s right,’ said Bobby. ‘Somehow he got me mixed up with John Hughes. I don’t know if Bertie was ever in any report. That incident was laughable. The bold Bertie just stood his ground and the ref crumbled. Och, that bloody guy couldn’t get anything right.’

The misery continued for the Celtic players when they discovered the board of directors had decided to fine every player £250. ‘That was our bonus for our League Cup win over Dundee,’ said Gemmell. ‘The club said they weren’t happy with our conduct and announced they would be withdrawing the cash and giving it to charity. We had been subject to the most degrading stuff from a shower of animals – yes, I agree with Alf Ramsey, too – and now we were being fined for our troubles. It was like all our nightmares had come at once.’ Gemmell, with that knowing smile, added, ‘Lisbon will live forever, though.’

Glasgow, Lisbon, Kiev, Buenos Aires, Montevideo. Yes, 1967 had been quite a year of discovery.

* TOMORROW: JOCK v RANGERS. The real story behind the scenes of the Celtic manager’s thoughts on the men from Ibrox – and the incredible Old Firm battlesin another dramatic and exclusive instalment from Alex Gordon’s ‘CELTIC: The Awakening’ – only in your champion CQN.