CQN continues it’s dramatic and EXCLUSIVE extracts from Alex Gordon’s book, ‘That Season In Paradise’, which takes you through the months that were the most momentous in Celtic’s proud history.

Today, we take another in-depth look in another thrilling instalment during an unprecedented and glorious campaign.

SCOTLAND’S footballing rulers, applying the identical reasoned judgement as that of General George Armstrong Custer at the Battle of the Little Bighorn, decreed that champions Celtic should kick off the new 1966/67 league season with the opening game against Clyde at Shawfield.

So, thanks to the muddled thinking of the decision-makers at Park Gardens, where common sense was a distinct rarity, Jock Stein’s triumphant side were denied the opportunity of an afternoon of colourful celebration, a gala event for their loyal supporters following a twelve-year odyssey of First Division suffering and torment. There would be no opening-day acclaim at a sell-out 60,000 capacity arena with the fans eager to pay their rapturous respects to their heroes. The cherished league flag would remain unfurled and in mothballs for another day. Instead, the club were told they would begin the defence of their newly-won title with a confrontation against a collection of keen part-timers at a rusty, rundown ground that doubled as a dog track.

So much for pomp and ceremony.

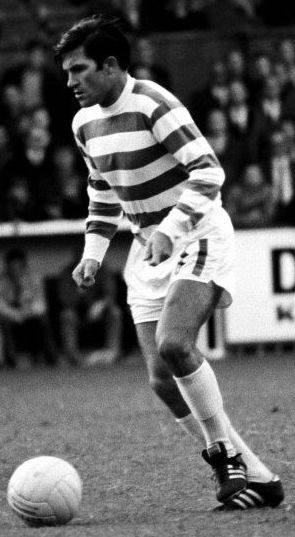

When the action got underway, however, there was no mistaking the gritty combination of enthusiasm, passion, verve and zest displayed by the Celtic players. It was obvious they were in the collective mood to pour every ounce of energy into the creation of something wonderful. They were two goals ahead inside twenty minutes and didn’t ease up throughout another lop-sided skirmish. The opening goal came in the tenth minute when Joe McBride, displaying his range of attacking skills, turned provider when he drew John Wright from his goal and passed neatly inside for Stevie Chalmers to sweep the ball into the inviting net. It was Celtic’s tenth goal in three games against gallant opposition in the space of only twenty-four days following the League Cup romps.

Eight minutes later, McBride added another; a vicious effort from a cross from John Hughes following a good run down the left flank from the tantalising winger which exposed the Clyde rearguard. Surprisingly, the supporters had to wait until the seventy-fifth minute before they witnessed the third goal. Chalmers, demonstrating the fact he had started his career as a winger, got wide before hurling in a hanging cross and Hughes, who always insisted he wasn’t particularly good in the air, got up superbly to launch an unsaveable header beyond Wright. In between the second and third goals, Celtic had struck the woodwork three times, had two efforts scrambled off the line and over-worked goalie Wright made a handful of decent stops. Everything had gone according to plan, but Bertie Auld had reason to feel a trifle tentative as the referee prepared to bring the contest to a halt. I co-authored the legendary player’s autobiography, ‘A Bhoy Called Bertie’, and here’s his memory from that game.

‘So, there I am, pinned against the dressing room wall with Big Jock’s massive left hand around my throat and he is threatening to wallop me with his right. If he was trying to get some sort of message across, it was working, take my word for it.

‘We had just come off the pitch after beating Clyde 3-0 at Shawfield and I knew our manager wasn’t greatly enamoured with some of my antics. My sin? I sat on the ball three times during the game. Okay, it’s a highly unusual ‘tactic’ when you are hoping to tempt a team into your own half. Clyde, though, refused to budge that afternoon. We were three goals ahead and you might expect them to open up and have a go at grabbing some sort of salvation. Not that day. The Clyde players seemed wary of even crossing the halfway line. They appeared to be content to keep the scoreline as it was.

‘I chased back to the eighteen-yard line to collect a throw-out from Ronnie Simpson. I looked up and, sure enough, there were the Clyde players refusing to come out of their own half. Quick as a flash, I decided to sit on the ball, hoping to spur at least a couple of their players into action. Nope, they weren’t buying it. I got up, rolled the ball back to Faither and asked him to return it. He duly did and I sat on the ball again. Still nothing stirred from our opponents. I staged an action replay immediately and parked my backside on the ball for a third time. Still, Clyde didn’t want to know.

‘I looked around the Shawfield Stadium and the Celtic fans were cheering and applauding. They loved this piece of showmanship, but I wasn’t doing it to belittle our rivals. Genuinely, I wanted them to make a game of it and they just didn’t want to know. I glanced over at our dug-out and that was when I saw Big Jock in full ranting mode. Not a pretty sight. Now whoever designed the dug-outs at Shawfield would never win any award for services to architecture.

‘For a start, you had to take a step down to get into them and that left you getting a worm’s-eye view of the action. All you could see were the ankles flying past and there is no way you could actually witness the game unfolding. It was the worst view in the house. But there was Big Jock, with all his bulk, trying desperately to clamber out of that small, confined space. There was a slab of concrete across the top of the dug-out that acted as a roof. Jock slammed his head off it – not once, not twice, but three times – as he attempted to climb his way onto the track.

‘He was furious and I thought, “You’re for the high jump here, Bertie. Let’s hope he calms down at full-time.”I could always hope. There wasn’t a chance of that happening. Once Big Jock went up like Vesuvius it took an awful long time for him to come back to earth. Maybe a week or two!

‘When the final whistle blew, I took a gulp and headed for the away team’s dressing room. I wondered if there was any chance I could get a shower, get changed and get on the coach before Jock emerged. I prayed for someone to stop him and have a chat before he could get into the dressing room. Headbutting a speeding train would be preferable to incurring the wrath of Jock. I knew I was in for an ear-bashing, but I didn’t anticipate what happened next.

‘Jock, with that heavy limp from the injury that ended his career, stormed in behind me as fast as he could. Now, the pegs in the changing area at Shawfield must have been put up by some fairly tall joiner. They were so high up the wall we used to have to put Wee Jinky on our shoulders when he was hanging up his gear!

‘Big Jock must have thought it would be a good idea to hang yours truly on one of those pegs that afternoon. He grabbed me with that massive mitt of his and lifted me off the floor. “Put me down, boss,” I squeaked, as his clenched right fist looked a wee bit too close to my nose for comfort. “Don’t ever treat a fellow-professional in that manner,” he growled. My feet were dangling by this stage as I attempted to plead my case. Jock wasn’t interested. “Do that once more and you’ll never play for this team again as long as I am the manager.” Thankfully, after a while, he released his grip and I slumped to the floor.

‘Then he turned to Faither, who thought he was going to get away with his part in my impromptu ‘tactics’ of trying to entice our opponents to cross the halfway line. “The same goes for you,” said Jock. “You encouraged him.” At least, our veteran goalkeeper was spared being suspended by the throat for a minute or two.’

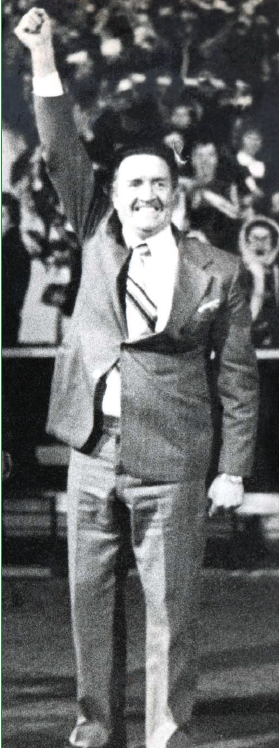

Following his ‘tete-a-tete’ with Auld, Stein met the Press to sum up the contest. ‘I was delighted with the team and the way we played,’ he said. ‘What pleased me most was the way we controlled the game. That’s what I want to see because it pleases me more than individual brilliance. We’ve got a lot of tough games coming up and that’s the standard I’m looking for.’

It was just a pity a mere 16,500 could pack into ramshackle Shawfield to witness the action. Joe McBride, incidentally, had scored a hat-trick three evenings earlier as the Scottish League overwhelmed their Irish counterparts 6-0. Bobby Lennox claimed two and Tommy Gemmell, Bobby Murdoch and John Clark also represented the Select. The inter-league meetings were abandoned due to lack of public interest in 1980. The Scots played the Irish on sixty-two occasions and were victorious on fifty-six of the meetings. The fans eventually grew tired of the lack of competition in these fixtures.

One encounter that would have certainly packed them in at Parkhead was the possibility of world-renowned Brazilian side Santos, with the acclaimed Pele in their line-up, performing in the east end of Glasgow on October 12. Santos were the footballing equivalent of basketball’s Harlem Globetrotters as a massive draw wherever they played. The news spread quickly among excited fans who were hoping for a glimpse of the player who was rated the most expert exponent of a football on the planet; the incomparable Pele. One observer likened a defender attempting to contain the South American genius as ‘trying to capture a shaft of light in a matchbox’. As ever, there had to be a snag; the Brazilians were demanding £50,000 in appearance money and expenses. Celtic chairman Robert Kelly politely declined.

Next up for Celtic in the harrowing early-season schedule, with the club’s first-ever performance in the European Cup against Zurich only a fortnight away, was an intriguing meeting with Dunfermline in the League Cup quarter-finals with the first game at Parkhead on Wednesday September 14. A crowd of 36,000 were in for a soccer treat as the players strutted their stuff throughout a first-half of an exceptionally well-drilled exhibition. Even the demanding Jock Stein couldn’t have asked for any more from his players during a forty-five minute display of near-perfection. Celtic were 5-1 ahead at the interval and heading for a complete wipe-out of the Fifers, rendering a second leg redundant. However, the manager would have words after a second-half dip that saw the opposition, almost on the floor in the first period, score twice with the final scoreline revealing a 6-3 triumph for the trophy holders.

For most of the evening, though, Celtic’s football was simply breathtaking, an absolute joy to witness. Five goals thundered behind the powerless Davie Anderson, Dunfermline’s up-and-coming prospect, in twenty-three flawless minutes from the home side as they rendered the opposition impotent in their feeble attempts to stem the merciless tide that flowed relentlessly towards their nineteen-year-old goalkeeper. He was picking the ball out of his net after only thirty seconds following a trademark soaring header from Billy McNeill following Jimmy Johnstone’s right-wing corner-kick. Anderson and his defensive colleagues hardly had time to recover before John Hughes clubbed in a long-range second in the fourth minute. The groggy Fifers, gasping for breath, were three goals adrift seven minutes afterwards when Bertie Auld scored the most spectacular counter of the evening. As ever, Bertie has a story to tell.

‘The fans must have wondered about my celebration that night. I have to say, in all humility, it wasn’t a bad goal. As I remember it, John Clark rolled the ball into my tracks around the halfway line and I was forced to veer to my right. Everyone knew my left foot was my stronger and I used to drive Big Jock potty by insisting, “Why do I need to kick the ball with my right when I’ve got a left as good as this? It does the work of two feet!” On this occasion, though, there wasn’t any room to manoeuvre the ball back onto my left foot, so there was nothing else for it but to have a belt at it with my so-called standing foot from about thirty yards.

‘The ball just took off like a rocket. I was as amazed as anyone when it arrowed high into the top left-hand corner of the keeper’s net. He made it look even more special with a fabulous, acrobatic leap across his line as he tried to paw it away. Some hope! That was a goal as soon as it left my boot. I raced over to the Boss in the dug-out and waved my right leg at him. There are some fairly crazy goal celebrations around these days, but that one has got to be up with the daftest. At least, Big Jock got the message and permitted himself a smile. Mind you, the fact we were now three goals up after eleven minutes might have had something to do with it, too.’

There was brief respite for the visitors, though, when Alex Ferguson pulled one back with a header, but normal service was restored when Joe McBride rattled in a penalty-kick in the twentieth minute after Jim Mclean had handled in the box. Three minutes later, young Anderson was helpless when Johnstone sneaked in an angled drive between the rookie keeper and his near post. It had been forty-five minutes of sheer splendour which was lapped up by the fans, myself included. What did the second-half hold in store after such a persuasive presentation from the men in green?

Apart from another fine strike from Auld – this time with his left foot – Celtic never touched the heights of the opening period. To be fair, Dunfermline, no doubt with the words of a furious manager Willie Cunningham ringing in their ears, showed a determination hitherto undetected in the first-half of this particular visit to the east end of Glasgow. They stuck another two beyond Ronnie Simpson to close the gap, but no-one at Parkhead that evening believed a dramatic fightback would be on the cards in the second leg, due at East End Park the following midweek.

Celtic had an important home meeting with Rangers in between the League Cup-ties and Jock Stein displayed Nostradamus-like qualities when he looked ahead to the visit of the Ibrox side. ‘It would be ideal to get off to the same sort of start that we enjoyed against Dunfermline,’ he said. ‘But you can never budget for these things in football.’

Inside four minutes, Celtic were leading 2-0 and the game was practically over. It was one of the most remarkable commencements in an Old Firm duel anyone could remember. Rangers had been humbled in Govan during the Glasgow Cup-tie the previous month and had made noises of retribution in the league. They didn’t even get out of the starting blocks. The occasion had barely got into motion when John Hughes sent Bobby Lennox scurrying into a dangerous area. Lennox, who helped himself to a hat-trick at Ibrox, became goalmaker on this occasion, flashing low ball across the penalty area. Joe McBride, unmarked smack in front of goal, swung a boot at the ball and connected with nothing more menacing than fresh air. Bertie Auld, however, was following up behind his good personal friend and he thumped a first-timer low beyond the stranded Billy Ritchie from ten yards, the ball ricocheting into the net off the base of the upright.

The hands on referee Tiny Wharton’s watch nudged just beyond three minutes played when Celtic doubled their advantage. And it was a masterpiece of precision, ingenuity and innovation by the masterful Bobby Murdoch. Jimmy Millar, the man dubbed the ‘Old Ibrox Warhorse’, banged into McBride to give away an obvious foul twenty-five yards out. Lennox touched it sideways to Murdoch who elected for power. His shot, though, bounced off the defensive wall and what happened next summed up the mindset of the peerless midfielder. Without breaking stride, the multi-talented Murdoch flighted an impeccable and delicate ball high towards the keeper’s top left-hand corner. Ritchie threw himself frantically at the attempt, but it was futile; the Celt’s improvised effort gracefully glid towards its destination. Parkhead erupted. A fair percentage of the 65,000 in attendance appeared to be enjoying the fare on offer. There were still eighty-six minutes to play, but, as everyone realised, the game was over as a contest.

Jock Stein took the team to his old stomping ground in the Kingdom of Fife for the return leg of their League Cup quarter-final and teenager David Anderson, the goalkeeper bombarded and traumatised in Glasgow only a week earlier, was left out with the unpredictable Eric Martin recalled. Celtic were forced to wait until the thirty-second minute to score on this occasion and, remarkably, it was the blond head of skipper Billy McNeill that again administered the punishment on the Fifers. Jimmy Johnstone swung over a right-wing corner-kick and, uncannily like the effort at Parkhead only seven days before, McNeill rose to bullet the ball beyond Martin. Caesar smiled, ‘I could have been the club’s leading goalscorer if we played Dunfermline every week!’

Stevie Chalmers sent in a swerving drive that completely confounded Martin as Celtic doubled their lead three minutes before the interval to move into an unassailable 8-3 aggregate lead. And the perplexed custodian must have wished his manager had kept faith in Anderson in the fifty-fourth minute when he fumbled the ball and that was all the invitation Chalmers needed to claim No.3 on the night. No-one seemed to notice – or care – that George Fleming had scored one for Dunfermline late on; by that time the holders were sailing towards the semi-finals. Rocks were ahead, though, in the league game against Dundee at Dens Park three days later.

Andy Penman, a thoughtful, old-fashioned inside-right, was the first player to send Celtic into unknown territory by going a goal behind in this most memorable of seasons. Penman, a genuine craftsman who never fulfilled his potential, also possessed a cannonball shot and he demonstrated this ability with the utmost perfection to Ronnie Simpson and Co’s annoyance in the twenty-eighth minute of a keenly-contested affair. Penman was allowed to line up an effort twenty yards out and he struck a devastatingly-accurate drive high over the Celtic keeper’s left shoulder into the roof of the net.

Tommy Gemmell recalled, ‘That goal was our fault. We had seen Penman hit those shots before and we should have closed him down immediately. Faither wasn’t too happy that we didn’t get out in time to charge down his shot. And I can assure you our goalkeeper would spare no-one’s feelings when he described our lack of defensive qualities is such instances. Thankfully, though, we were only behind for four minutes.’

The majestic Billy McNeill, matchless in aerial battles, towered above the Tayside defenders to nod on an astute free-kick from Bertie Auld, the ball bending beautifully to pick out the advancing run of the centre-half. McNeill headed it down, there was pandemonium in front of goalkeeper Ally Donaldson and Bobby Lennox thrived in this panic-stricken environment. As the ball bobbled around, he thrust out a foot and prodded it beyond Donaldson. It was never going to be a contender for Goal of the Season, but it was crucial on an afternoon when Celtic’s opponents were clearly in the mood to halt the progress of the green-and-white machine.

Only twelve minutes remained when the visitors claimed the winner after they were awarded a penalty-kick following defender Doug Houston’s handball in the box. It was a stick-on spot-kick, but there was a problem – Joe McBride had sustained an injury and had remained behind in the dressing room at the interval with Stevie Chalmers taking his place. So, who was going to take the award? McBride had tucked away five in flawless fashion and now it was someone else’s turn to take the responsibility.

Up stepped John Hughes, who had knocked in more than a few earlier in his career, including two in the 2-1 League Cup Final win over Rangers the previous year. Alas, Hughes’ accuracy deserted him that afternoon. Donaldson, a goalie who, throughout his career, had been linked with Celtic, got down athletically to push the ball away. Chalmers, however, saved the blushes of his team-mate and raced in to smash the rebound into the net. The strike put him into the history books as the first substitute to score a goal for Celtic, but Chalmers would be better remembered for another goal later in the same season.

However, before the date of May 25 1967 bore the slightest significance to anyone of a Celtic persuasion, there was the business of playing the club’s first-ever tie in the European Champions’ Cup against FC Zurich at Parkhead on the evening of Wednesday September 28 1966. The players had become used to Jock Stein producing the magnetic tactics board by this time, but, more often than not, the manager ignored the device when he was dealing with domestic games. He reckoned he was going over old ground discussing the merits of opponents’ systems and one thing Stein detested with a passion was having to repeat himself.

John Clark recalled, ‘When the Boss was talking tactics, I found I had to listen intently. He would speak fairly quickly in a lot of detail and if you didn’t catch what he had said first time around there was no chance of him backtracking. It was always the individual’s fault for not paying attention, according to Big Jock. So, we were normally a fairly hushed group of players when the magnetic board was produced.’

Jim Craig admitted, ‘I had an inquisitive mind and I would ask questions. This was something that was new to Big Jock and something he didn’t embrace with any enthusiasm. I was the guy who would query this, that and the next thing while most of my colleagues bit their tongues and kept quiet. He would point to the tactics board and go through a lengthy routine. Some of us took it in and others didn’t. How could you tell Jimmy Johnstone how to play?

‘I would ask a few questions, make a point or two and Big Jock, plainly, didn’t welcome such intrusions. He was a meticulous planner and would go through our line-up and tell us exactly what he expected us to do. I thought it was only right and proper that I should ask a question or two just to clear up any possible misunderstanding. If Plan A wasn’t working, what was Plan B? Jock didn’t like that. He was a big fan of the master/servant relationship and, naturally, I didn’t agree with that mode of thinking. So, when you queried something, Jock would wave you away with that big left hand of his. “Oh, just do as you’re told,” he would say. Okay, he was the manager, but that didn’t mean I had to touch my forelock every time I spoke to him.’

Tommy Gemmell said, ‘As I’ve mentioned countless times, Big Jock was scrupulous in his preparations. When he got the tactics board out we knew we would have to sit through half-an-hour or so of instructions as he moved the little magnetic dots around. He simplified everything for us as usual, and, as you would expect, he had done his homework on our opponents. Their biggest name was their player/coach Laszlo Kubala, who had been a player for Barcelona at the height of his ability. However, to be honest, the Hungarian was now forty-one years old and his best days were in the past. We knew, though, they had had six players in the Switzerland squad for the World Cup Finals in England that summer and, as champions of their country, they would be no mugs.

‘So, by the time the kick-off came around to our first leg in Glasgow we were fairly well primed as to what to expect from our first opponents in Europe’s blue riband competition. Or so we thought. What Big Jock hadn’t legislated for were the Swiss being a team of cloggers. They set out to kick us off the park that night and Wee Jinky, in particular, got some heavy treatment. To be honest, we didn’t see it coming and Jock hadn’t anticipated it, either. There were some nations that would produce so-called nasty pieces of work, players and teams who concentrated on the physical side of the game. No-one predicted FC Zurich from Switzerland being one of those teams.’

Kubala, a clever and astute forward who scored 194 goals in 256 appearances for Barcelona between 1951 and 1961, had transformed the Swiss team after taking over earlier in the year. They were quite brutal in their treatment of opposing players which was in direct contrast to the way Kubala performed as a footballer. Danish referee Frede Hansen allowed a lot of challenges to go unpunished and there can be little doubt the Celtic players were knocked out of their stride by the unexpected approach by the Swiss.

The wiles and promptings of Bobby Murdoch and Bertie Auld in the middle of the park were being suffocated, Joe McBride and Stevie Chalmers were getting little joy in the centre of the attack against a defence that employed a sweeper, still a relatively new ploy outside Italy at the time, and Jimmy Johnstone and John Hughes were making no progress on the flanks against tenacious full-backs who stuck to their task with grim ferocity. As the contest unfolded, the 47,604 audience realised competing in the upper echelons of European football was a lot different from performing in the domestic game. It may have been even worse because Ronnie Simpson had been forced into action to produce a stunning stop shortly after kick-off.

In his 1967 memoirs, ‘Sure it’s A Grand Old Team To Play For’, the keeper recalled, ‘I had probably my best save of the entire European Cup competition in the early minutes. Zurich’s Italian inside-forward Rosario Martinelli came through fast and hit a shot at goal which swerved in flight. I had to change direction as I went for the ball and was fortunate to get one hand to it to save the troublesome effort.’

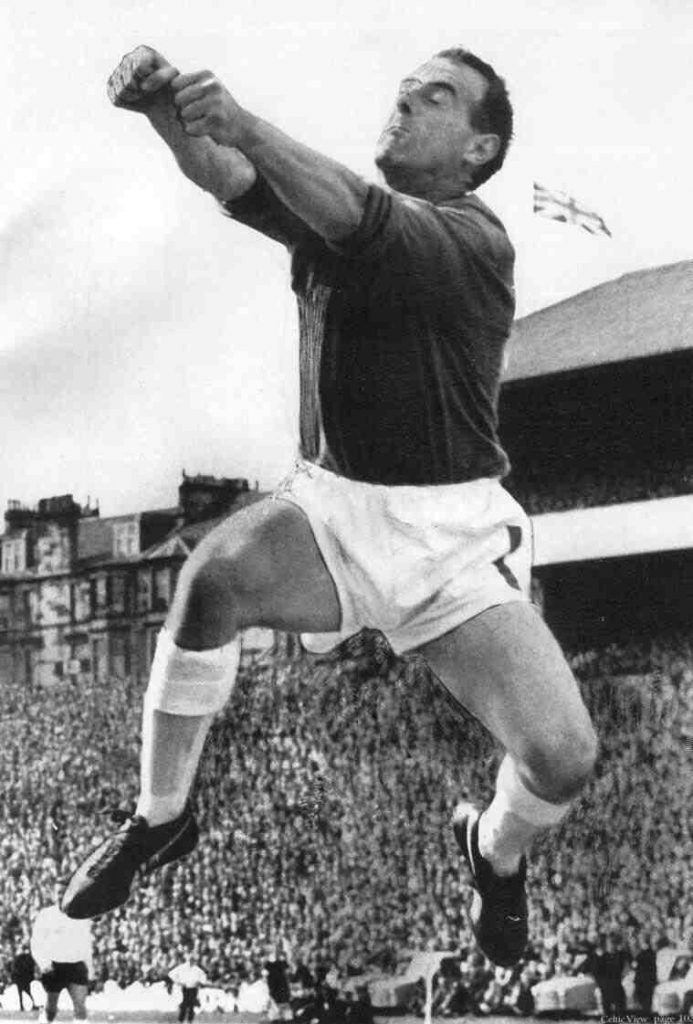

It was still goalless after the hour mark and the crowd was beginning to get more than just a little bit anxious. The Swiss players swarmed around the pitch as they nullified the threats of the opponents who had been clearly pinpointed by their player/coach Kubala, sitting only yards away from Stein on the trackside. Someone, though, must have overlooked the pulverising power Tommy Gemmell possessed in both feet, mainly his right. The clock ticked towards the sixty-fourth minute when John Clark, tidy and efficient as ever, halted a rare Swiss attacking foray and knocked a neat ball out to Gemmell, playing at right-back that evening with Willie O’Neil on the left.

The defender with the cavalier attitude, a few yards inside enemy territory, nodded the ball forward and must have been surprised – and delighted – there wasn’t a posse of opponents immediately surrounding him as he moved into attack. The Zurich defenders made their biggest mistake of the evening and backed off as Gemmell continued his surge forward. Celtic fans, with a reasonable certainty of what was about to transpire next, held their collective breath in anticipation. The adventurous Celt took a swift look up, got his eye-to-ball co-ordination absolutely spot on, and swung his mighty right boot at the spherical object that simply took off from twenty-five yards and blazed its way into the keeper’s top left hand corner of the net. Steffen Iten hardly moved a muscle as the missile zeroed in on its target.

Celtic Park bounced with the combination of joy and relief as the fans welcomed their team’s first-ever goal in Europe’s top-flight competition and, a mere five minutes later, they were hugging each other again as Joe McBride doubled the advantage. Clark, once more with his uncanny anticipation, broke up a Swiss raid and rolled a short ball to Gemmell who knocked it inside to McBride. The striker, who had been shackled up until that point, sensed danger. He played a swift one-two with Auld, who wrong-footed the Swiss defenders with a snappy back-heel to his team-mate. McBride, from the edge of the eighteen-yard box, whacked the ball and it took the merest of touches off a lunging defender as it swept beyond the bewildered Iten. Cue pandemonium in Paradise.

The game ended in a controversial note, though, when it looked as though McBride had claimed a third goal. Certainly there was nothing wrong in the manner in which he scored and there was no question of him being offside. However, referee Hansen signalled the game was over and thousands of puzzled supporters emptied out of Celtic Park wondering if their favourites had won 2-0 or 3-0. It transpired the over-fussy match official had blown his whistle just as the ball had been crossing the line. The Swiss, with their obsession for precision timing, would no doubt have applauded the intervention of the punctilious Dane.

The FC Zurich players left Glasgow the following morning naturally grateful their task at overturning the deficit at their Letzigrund Stadium the following Wednesday had been rendered a lot less difficult by a highly dubious decision by the referee. It was only a matter of time before they would become Celtic’s first European Cup victims on the Glasgow club’s invigorating march towards history.

TOMORROW: OCTOBER – ON THE VERGE OF SOMETHING SPECIAL