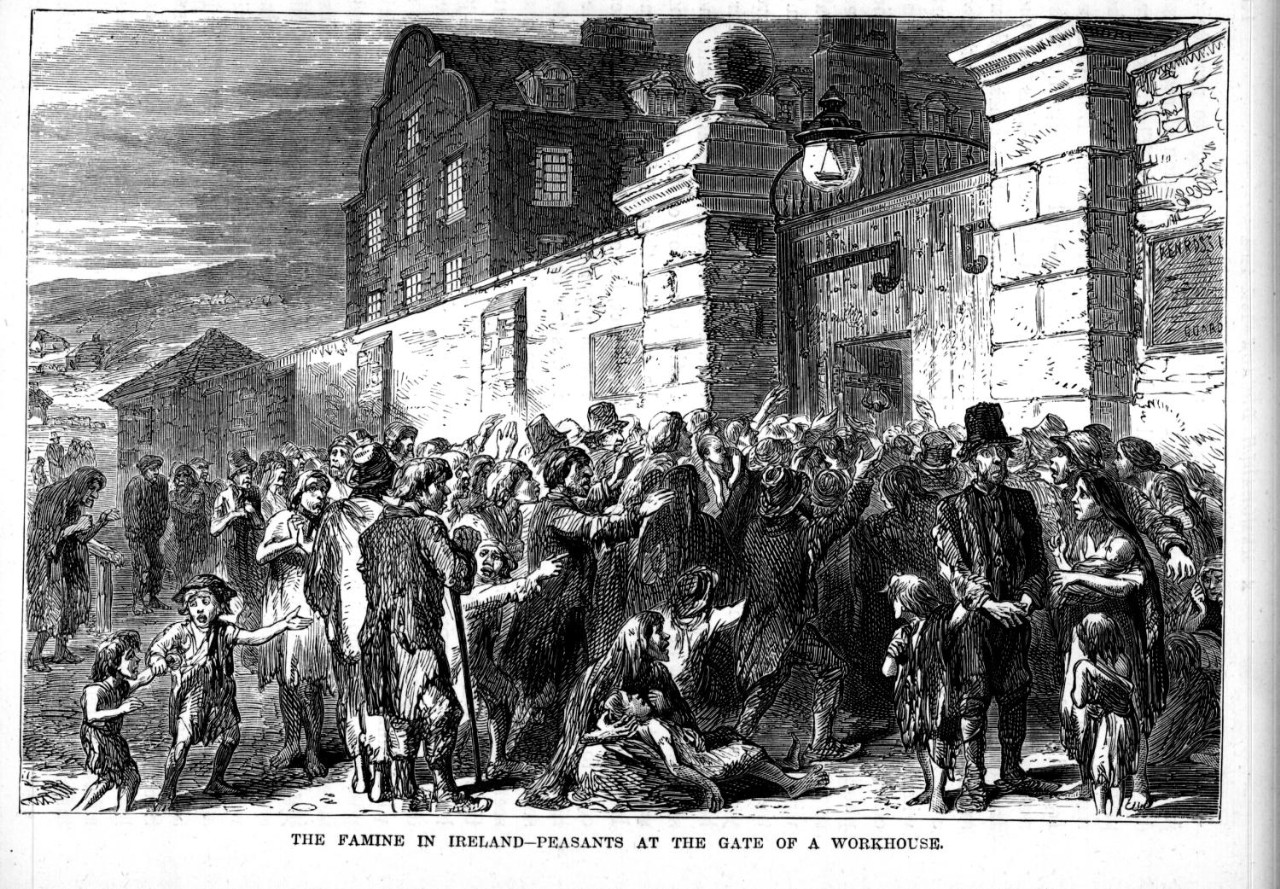

CELTIC WAS FOUNDED TO HELP THE IRISH CATHOLICS OF GLASGOW WHO HAD LEFT THE OLD COUNTRY TO ESCAPE THE RAVAGES OF THE FAMINE, ONLY TO FIND POVERTY EVERY BIT AS BAD. THEY AND THOSE THEY LEFT BEHIND ARE REMEMBERED IN MANY PARTS OF SCOTLAND, PARTICULARLY AT CARFIN. HERE PENSIONERBHOY LOOKS AT THAT SPECIAL PLACE.

I recently read an article by Joe O’Rourke, on the C.S.A. Forum, reminding Celtic supporters of the Irish-famine mass at Carfin Grotto. I trust that those who attended to honour and pray for those who suffered back then, were aware that the Grotto in which they stood was the product of the dedication and hard labour of local men and women, many of whom were descended from those very victims. The story of The Grotto is one of good emanating from insidious circumstances; a story about downtrodden people preserving their dignity in the midst of inhumanity. This will be no history lesson but rather a few personal recollections. I direct any reader attracted to a proper history of Carfin to the more accurate and extensive works of the architect of The Grotto himself, (Mgr Thomas N. Canon Taylor “Carfin Grotto – The First Thirty years (1922-1952)”) or to his definitive biography by Susan McGee M.A., “Monsignor Taylor of Carfin”.

The central character in the tale of Carfin Grotto is undoubtedly Father Thomas Nicholas Taylor, later Monsignor Taylor. When promoted to the rank of canon, his parishioners affectionately christened him simply The Canon. In 1915 he was appointed to the mission parish of St. Francis Xavier’s, Carfin, incorporating the Catholic missions of Newarthill (now St. Theresa’s), New Stevenson (now St. John Bosco’s), Cleland (now St. Mary’s) and Jerviston. He ‘ruled over’ St. Francis Xavier’s till shortly before his death in 1963. Recalling my close contact with The Cannon has sparked a few memories of him and of other people and events in Carfin that may provide some interest or raise a smile. If nothing else, I hope it brings a small piece of paradise in the heart of central Scotland to the attention of those who, as yet, are not aware of it.

Anyone who happens upon the Carfin story quickly realises this unremarkable Lanarkshire mining village came to prominence through the creation of the ‘Lourdes’ Grotto and the notoriety of Monsignor Taylor. The Grotto was conceived by The Canon as an ‘occupational distraction’ for the many unemployed of the area suffering the frustrations and hardships of the twenties and thirties, due initially to the coal miners’ strike of 1921 and later the Great Depression. It was born of his desire to ‘keep them off the streets’ and when he had ‘a will’, he most certainly had ‘his way’. No one did ‘walking away’ with The Canon.

Canon Taylor developed a reputation somewhat in keeping with his name. At Sunday processions it boomed like a cannon and he was known to explode with the same impact as the substance suggested by his initials T.N.T. Among us kids, he was nicknamed “Dynamite”. I can personally vouch for his ‘outbursts’ having often been at the receiving end of them. On one occasion when, unfortunately too slow to escape his attention after morning mass, I was instructed to wait for him in the chapel. I remained there impatiently but I dared not leave. 8.30am passed as did 9.30 and 10.30. Those were the days when going to communion meant fasting from midnight. This on its own was an enormous challenge for the appetite of a growing boy without the added torture of waiting an additional two hours or more to eat.

For me such hunger equated to ‘the agony in the garden’ and though I could claim to be a devout follower of Jesus, I eventually concluded that on that morning I was sharing His suffering for far too long. I fled the chapel and made my way to my father’s nearby workplace for a desperately needed bite. I doubt I had even sat down before there was the threatening stomp of leather shoes and the rustle of a black cassock fast approaching. It was eerie the way The Canon always seemed to know where you were.

The next few minutes were a T.N.T. tirade of ‘get behind me Satan!’ in thundering tones accompanied by fist-banging, the specific products of fire-and-brimstone-styled preachers of the pre-Vatican Council era. I was mercilessly condemned for leaving The Lord’s presence and for disobeying the parish priest’s request, to me more like a death-threat command. The subsequent punishment was walking round The Grotto till together we had completed all fifteen (the wee beads are only a third of the whole) decades of the rosary, the litany of the saints and The Canon’s add-ons of which there seemed to be millions. The hefty tomes of “The Lives of the Saints” containing many hundreds of fictitious holy people are a mere trickle compared to The Canon’s reservoir. I may have been given further penances but I think my brain and possibly my Catholicism simply switched off. Since I live to tell the tale, I presume I eventually ate but, to this day, I have never found out why he asked me to wait in the first place.

This is no more than a snippet from the life of the man who began it all and who, assisted by numerous others, completed and continued to develop the famous shrine throughout the remainder of the twentieth century. Though it is still located in the village and remains known as Carfin Grotto, it is sadly no longer the valued singular possession of the parish but now comes under diocesan jurisdiction. In fairness, I am not sure the parishioners of today put the same store by it as their forebears did.

I doubt that anyone would question the assertion that the ‘hay-day’ of The Grotto was approximately from the late forties through to the early sixties. Saying that, as early as 1924 The Canon recorded a single pilgrimage of over fifty thousand in one day. Mind you, like the Celtic board over the years, he could be prone to doctor attendances to fit purpose. But there is no doubt he was the driving force behind The Grotto’s spirituality, publicity and popularity. As a boy in the fifties I remember special trains just for pilgrims running to and from Carfin Halt on Sundays and this at a time when there was no official Sunday passenger services. Hundreds of buses carrying pilgrims from all over the British Isles filled car parks and clogged streets in Carfin and neighbouring villages. There were dozens of police on traffic and crowd control duties. The village shops were generally closed on Sundays except for a few cafés doing fish and chips and there were no proper restaurants.

A large parish hall, The Lourdes Hall, adjacent to The Grotto, provided limited refreshments thanks to local volunteers. Picnics were the main order of the day for many pilgrims. They had to dine on the ash of the car park as it was somewhat niggardly forbidden to use the grassy areas of the Grotto itself. Some villagers, handily located, set up temporary ‘tearooms’ in their front gardens, porches and doorways as a charitable gesture towards pilgrims caught short by the lack of facilities or maybe it was just to make a fast buck. Susan McGee, in “Monsignor Taylor of Carfin”, describes in greater depth these people, these times and the growing popularity of The Grotto.

Over the years, hundreds of men, not just from Carfin but from many nearby villages and the surrounding area, volunteered their labour to building and looking after The Grotto. Stories were told of disputes and varying opinions as to who could and could not take credit for the different work. Rumours abounded about whether certain individuals assumed positions of authority rather than being designated them. However, in spite of the apparent discord, there was sufficient harmony to see the original Grotto completed and officially opened in 1922. Considering the strenuous and potentially dangerous nature of the task, the commitment to unpaid work was more than commendable. It was said that, whenever he could, The Canon provided a bonus of a bag or ‘poke’ of imperial mints and five Woodbine cigarettes to each worker on the day.

Though it was widely told, I myself can not verify this story. But I do know that it was in the giving nature of the man to offer all that he could to those in want. The same Canon who tongue-lashed me for leaving the chapel, also gifted me a pair of shoes when my mother could not afford much needed new ones. Perhaps this was a symptom of the community spirit back then too. There was a musketeer-type camaraderie that was reflected in a social ethic of ‘one for all and all for one’, not dissimilar to the selfless charitable activities of the Celtic family. Maybe that was the real driving force behind the volunteers who gave so much, one man his life, to build a tribute to Mary that was also a haven for all in turbulent times.

I knew a number of the ‘Grotto Workers’, though, sadly, many in their twilight years, men and women whose faces reflected the hardship of their existence but also their commitment to their faith and a pride in their accomplishments. Usually they would only have experienced the devil-child in me but I trust that on occasion they received my respect and admiration. I witnessed for myself and heard tales of the outstanding feats of these exceptional folk. In a world of strife, a world of avaricious inhumanity, a world of moral decay, their achievements were beacons of decency lighting up a degenerate landscape. Their monument to Our Lady at Carfin, provides a few acres of heaven in an often hellish environment. I hope The Grotto continues to be a fitting tribute to their sacrifices.

These few recollections are intended to highlight a particular bit of good that sprung from the greed and perverseness of coal barons. Could the conflict in the Scottish pits and mines in the early twentieth century be mirrored today in the turmoil within Scottish football, caused primarily by the excesses and depravity of one wayward club? Hopefully, someone in authority, with vision and foresight akin to that of Mgr. Thomas Nicholas Canon Taylor, ‘Dynamite’, might step forward to offer a solution or, if not, to at least create an outlet for the frustrations of those who feel aggrieved. Meanwhile, it is comforting to know that in an area of Scotland more renowned for its intolerance and division, there is a little piece of paradise where one can reflect and regain some peace of mind.

“Set in the midst of a small village, the Grotto represents the achievements of hard-working people whose faith directed them to create a holy place in the industrial belt of Scotland.” Wikipedia.

Initially published in Issue 9 of CQN Magazine.